Bees come in all colors, shapes and sizes from the large carpenter bees to the tiny

Perdita minima. Over 4,000 species of native bees can be found in the United States along with hundreds of non-native bees like the honey bee. Honey bees were introduced from Europe and now assist our native bees and other pollinators with the task of pollinating flowering plants. Surprisingly, honey bees are not effective pollinators for many native plants like cherries, blueberries and cranberries. So, attracting a variety of bees to your yard, particularly those which are native, will help with all of your pollinating needs.

Bee Basics

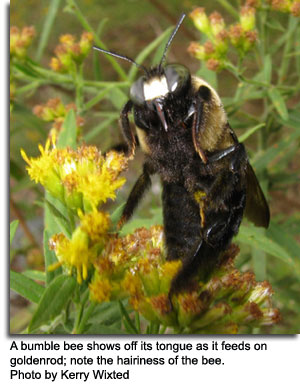

Bees are considered to be insects, and like all other insects, bees have a head, thorax and abdomen. Bees also have six legs and two pairs of wings. On their head, bees have well developed antennae that allow them to feel and “smell” as well as five eyes: two large, compound eyes and three smaller, simple eyes. Bees also have mandibles used for a variety of tasks from biting to sculpting pollen and digging. In addition, bees have special tongues that are either long or short, depending on the shape of the flower they visit to consume nectar. The wings and legs of bees are attached to its thorax which connects to the abdomen. The bee’s abdomen is segmented with female bees possessing six segments and males possessing seven segments. Only female bees have a stinger which attaches to the abdomen. The stinger is actually a modified ovipositor or egg-laying device.

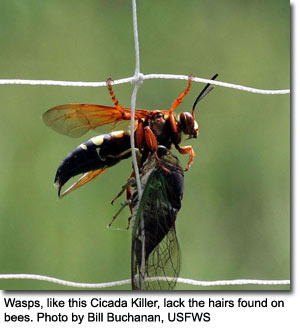

Bees are often mistaken for wasps, which tend to be more aggressive. Bees, for the most part, are hairier than wasps due to their need to gather pollen. Wasps, on the other hand, are predatory and lack pollen collection adaptations. Wasps also tend to have “thinner” bodies compared to bees. One notorious wasp is the yellow jacket which builds ground nests.

Nesting

All bees need nests, and bee nests are just as variable as bees themselves! Just about all bee species build their own nests aside from Cuckoo bees which lay their eggs in the nests made by others. Some bees are miners which select open, sunny areas to excavate a network of tunnels underground to lay their eggs. Other bees, like masons and leafcutters, nest in holes. Many of these species take advantage of holes made by other insects like beetles to construct their nests. In contrast, carpenter bees design their own abodes by burrowing in wood. Most of our native bees are solitary nesters; each bee builds her own nest and does not share with others of her kind. European honey bees are colonial, centering their complex society around a queen. Paper wasps and yellow jackets are also colonial.

Bee Families

Maryland is home to around 400 different species of native bees. There are five common families of bees found in Maryland. These families include Apidae (Honey Bees, Bumble Bees and allies), Halictidae (Sweat Bees), Adrenidae (Miner Bees), Megachilidae (Leaf-cutter Bees, Mason Bees and allies) and Colletidae (Plasterer Bees).

Apidae: Apidae is the largest family of bees, and it includes both species native to Maryland as well as non-native species like the honey bee. Bumble bees belong to this family. They are large, furry bees that are mostly black in color. Bumble bees nest in the ground but can sometimes be coaxed to nest in boxes on the ground. Bumble bees strongly resemble Carpenter bees which excavate holes in wood. Carpenter bees, however, do not have a hairy abdomen like bumble bees. Apidae also contains Squash bees, which as their name suggests, are specialized pollinators of squash and other plants in the Cucumber family (pumpkins, melons, cucumbers, etc). Cuckoo bees are also in Apidae. This large group of bees are parasitic red or yellow bees that do not pollinate flowers because they rely on other bees to care for and feed their young. Female Cuckoo bees lay their eggs in the nests of others, and the resulting young kill and eat the host bee’s larva.

;

;

Halictidae: Halictidae contains some of the most colorful bee species found in Maryland. These bees have shiny, metallic-colored bodies and nest mostly in the ground. Some Halictid bees are known as “Sweat bees” as they are attracted to salts found in human perspiration. Generally, a gentle swipe from the side will cause these bees to leave people alone; however, if females feel threatened then they might deliver a mild sting.

Andrenidae: Andrenid bees are also known as miner bees, which, as their name suggests, nest in tunnels underground. Miner bees can be identified by a velvety patch of hair between their eyes and antennae. These bees are some of the earliest bees to emerge in the spring and several of the species are adept at pollinating azaleas and/or apples.

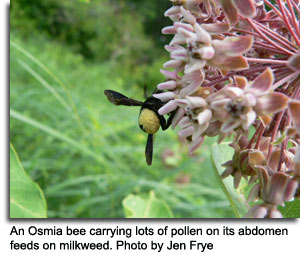

Megachilidae: This family of bees includes mason bees and leaf-cutter bees. Most Megachilid species nest in holes found in wood, and several species are easy to coax into using wooden nest boxes. Interestingly enough, bees in this family tend to carry pollen on their bellies rather than in pollen sacs on their legs or abdomen. One particularly important species in this family is the Blue Orchard Bee (Osmia lignaria).

Colletidae: Colletids are solitary bees which nest in pithy stems of plants. Many of these species of bees lack the hairiness of other bees, sometimes causing them to be mistaken for wasps.

Bee Conservation

Honey bees, both in the wild and in colonies, are dying at unprecedented rates due to Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD). At this time, the underlying cause for CCD is unknown; however, it is believed that a combination of pesticides, stress, disease and malnutrition is leading to CCD. In addition to CCD, recent research in California has found that honey bees are becoming “zombie-like” after a parasitic phorid fly lays its eggs on them. Both CCD and the parasitic fly are a large concern for people as nearly one third of agricultural crops in the United States are pollinated by honey bees. The parasitic phorid fly also attacks bumble bees.

In addition to these threats for the honey bees, our native bees are also declining in numbers. Some of the declines are attributed to the loss of native plants to feed on while others are due to the widespread use of broad-spectrum pesticides. As a consumer, you can make a difference by planting native species of plants in your yard as well as discontinuing the use of pesticides, aside from using select organic-approved pesticides found in the list below under Bee Resources.

Any thing you do to help bees will also help our other beneficial pollinators and the plants that depend on them. A little assistance for our smallest creatures can help conserve a whole ecosystem!

What You Can Do

- Plant a pollinator garden. For ideas on plants to include,

click here.

- For tips on how to create a Bee Friendly Backyard,

click here.

click here. - Avoid pesticide use in your yard and encourage

beneficial bugs to use your yard.

- Provide water in a shallow saucer for bees.

- Provide nesting habitat. Check out the Xerces Society fact sheet on

Nests for Native Bees.

Nests for Native Bees. - Educate others!

How to Build a Bee House

Materials:

Materials:

- 7" x 7" x 7" block of untreated wood

Construction:

-

Drill holes in the block, spaced 3/4" apart.

- For leafcutter bees, the holes should be 1/4" wide and 2 1/2 -4" deep.

- For mason bees, drill 6" deep, 5/16" wide holes. Do not drill completely through the block.

- Place block on the side of a house or shed, beneath the eave, or mount it securely on a fence post or pole at the edge of the yard. Attach an overhanging roof piece to the block if placed away from an overhang or building eave.

- Block should be erected in early spring and placed at least three feet above the ground.

- Position block to face southeast, allowing it to get morning sun. During the winter, you can take your box down and place it in an area like a shed to protect the larvae from the elements.

After two years, it is best to retire your wood block to prevent buildup of diseases and parasites. Take your nest block down and place it in a 5 gallon bucket with a lid and a small quarter-sized hole drilled in the top. Leave the block and bucket outside in a covered area to allow the bees to emerge. Once all of the bees have emerged, you can retire your block. If you leave the block up, there is a potential more bees will colonize it.

Avoiding Bee Stings

Bee stings are not a pleasant experience, especially if you are allergic. However, by using some simple precautions, bee stings can be avoided. While male bees can sometimes exhibit aggressive behavior, they cannot sting. Only female bees have stingers. Bees will sting if they feel threatened or if they are defending their nest. Moving slowly and calmly around bees will reduce their reaction. Avoiding conflict or disturbance around a nest will reduce the chances of getting stung. If you locate a bee nest in or around your property, give it a wide berth. If you have to be near it, move calmly and don't make any sudden or jerky movements. Avoid wearing strong-scented colognes or perfumes which attract bees as well as bright, floral prints.

If you get stung by a bee, then remove the stinger (if from a honey bee) as quickly as possible. Try not to squeeze the venom sac attached to the stinger; brush or gently scrape the stinger sideways, using a tweezers or finger nail, until is slides out of your skin. Wash the area with soap and water. Apply ice or a baking soda/cold water paste to the area to deal with swelling. Localized swelling and redness are a normal reaction to a bee sting. An allergic reaction goes beyond the immediate stinger site. If an allergic reaction results, then contact a health professional immediately.

Bee Swarms

Occasionally, honeybee colonies will swarm in an attempt to find a new location for their colony. This often happens in the spring and is rarely a danger to people. In the event of a swarm, you can contact a local member of the

Maryland State Beekeepers Association.

Bee Resources:

Invite Wildlife to Your Backyard!

For more information, please contact:

Maryland Department of Natural Resources

Wildlife and Heritage Service

Tawes State Office Building, E-1

Annapolis MD 21401

410-260-8540

Toll-free in Maryland: 1-877-620-8DNR

[email protected]

Acknowledgements:

- Honeybee on buttonbush by Jennifer Frye

- Bumblebee by Kerry Wixted

- Cicada Killer by Bill Buchanan, USFWS

- Bumble bee pollinating buttonbush by Jennifer Frye

- Halictid bee by Kerry Wixted

- Andrena bee by Richard Orr

- Blue Orchard Bee by John Brandauer

- Bee on purple coneflower by Ryan Hagerty, USFWS

- Osmia bee by Jennifer Frye