History of Sandy Point State Park

American Indians and Captain John Smith

Though no American Indian archeological sites are known to exist on Sandy Point State Park, the surrounding area was home to Algonquin-speaking peoples during the centuries prior to European exploration and settlement. However, due to raids from the Susquehannocks and Massawomecks, who had settled in the upper Chesapeake, the Algonquin-speaking people moved further south and inland toward the Patuxent River in the late 1500s. When English explorer Captain John Smith explored the area in 1608, there were no American Indians living in the immediate area.

Captain Smith noted the area was well-watered, with high barren cliffs, but fertile valleys. The woods, he noted, were inhabited by many animals that no longer call the Chesapeake Bay home, including wolves and bears.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) maintains an interpretive buoy at the mouth of the Severn River. It tells the story of Captain Smith’s exploration of this part of the Chesapeake Bay.

To learn more about the buoy, please visit:

buoybay.noaa.gov/locations/annapolis#quicktabs-location_tabs=1.

Tobacco Farming and Enslaved Labor

The Broadneck Peninsula, where Sandy Point is located, was settled by English colonists in the mid-1600s. The first colonists lived hard-scrabble lives growing tobacco near the Chesapeake Bay and its tidal rivers. Some earned enough wealth to purchase involuntary labor -- first English indentured servants, later enslaved Africans.

When Maryland moved its capital to Annapolis in 1695, prominent families, such as the Sharpes and Homewoods, consolidated their holdings into large estates. By the time of the American Revolution, tobacco still dominated the regional economy, and most labor was performed by enslaved African Americans.

Early maps indicate that Sandy Point was originally called “Rattlesnake Point,” but the present-day name took hold by the late 1700s. The origin of the name “Sandy Point” is unclear, but it is likely a reference to its sandy beach and offshore sandy shoals.

In the early 1800s, Sandy Point was part of a large estate under the ownership of Horatio and John Gibson. In 1818, the Gibsons sold the farm to Henry Mayer. In 1820, Mayer held 22 enslaved African Americans who toiled in tobacco and grain fields to create the wealth their owner enjoyed. When Mayer died in 1833, a property inventory listed "a large, two-story, brick dwelling house with wings of brick, a barn, Negro quarters of brick, a carriage house, stable and a granary of wood." The farm, appraised at $7,000, also contained two large orchards. The “brick dwelling,” likely built by Mayer, is now the

Sandy Point Mansion.

Wealthy Baltimore shipmaster Baptist Mesick purchased the property in 1833 as a retirement estate. Mesick lived another three decades before passing in 1863. During his tenure, the farm shifted away from tobacco cultivation to grains and other crops, notably watermelon, strawberries and pumpkins. This agricultural and economic shift led to a decline in the number of enslaved laborers. During the U.S. Civil War, William Evans, an enslaved resident of Sandy Point, liberated himself by escaping and initially joining the U.S. Colored Troops (Union Army) before serving in the U.S. Navy.

Sandy Point Shoal Light Station

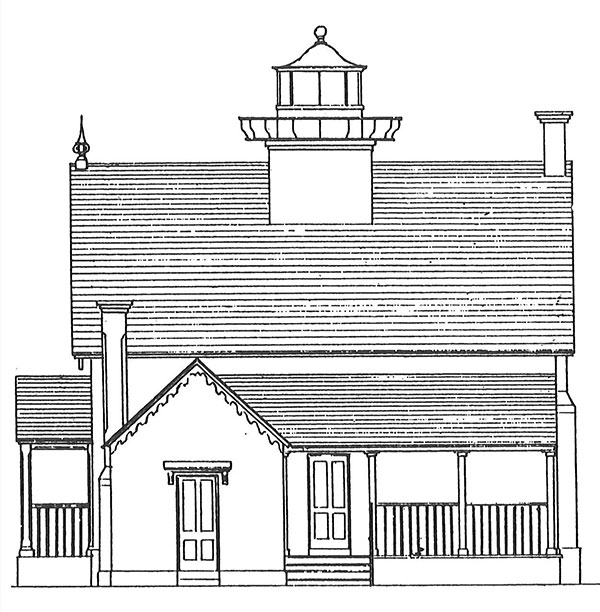

A drawing of the original lighthouse - Image: National Archives, PhiladelphiaIn 1857, the United States Lighthouse Board erected a brick lighthouse on the shore of Sandy Point. The 35-foot tall tower was incorporated into the keeper’s two-story, four-room residence. The shoreline lighthouse, however, proved ineffective and the present-day

caison-style light station was built offshore in 1883.

Until 2019, the offshore light station lit the way for safe passage through the perilous sand shoals at Sandy Point. An excellent surviving example of the caison-style lighthouses that were built throughout the Chesapeake Bay, the Sandy Point Shoal Light Station was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2002. Today the lighthouse is privately owned and is not open to the public.

From Horse Farm to Segregated State Park

In the early 1900s, Sylvester Labrot, a successful businessman from New Orleans, acquired the property. His son, William H. Labrot, a sports enthusiast and politician, renamed the property “Holly Beach Farm,” and made it one of Maryland’s most successful horse breeding farms.

In 1949, Labrot sold 685 acres of his farm to the State of Maryland for the purpose of building a new park. Sandy Point became the first bayside state park located near Annapolis, Baltimore and Washington, D.C. Over the next three years, several state government agencies partnered to plan and build the park.

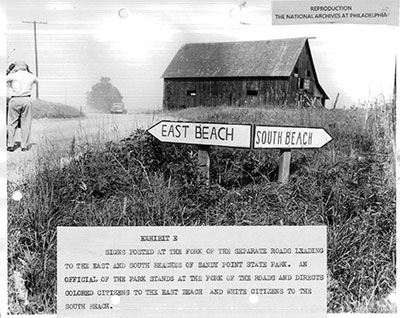

When Sandy Point State Park first opened to the public on Fourth of July weekend 1952, its two beaches and bathing facilities were segregated by race: only white patrons could use the expansive South Beach while Black patrons were relegated to the smaller East Beach. Initially, the East Beach restrooms were smaller and the beach itself was muddy and covered with rocks and debris.

Signs posted at the fork of the separate roads leading to the east and south beaches of Sandy Point State Park. An official of the park stands at the fork of the roads and directs colored citizens to the east beach and white citizens to the south beach.

Signs posted at the fork of the separate roads leading to the east and south beaches of Sandy Point State Park. An official of the park stands at the fork of the roads and directs colored citizens to the east beach and white citizens to the south beach. |

Children on the east beachfront.

Children on the east beachfront. |

Photos: National Archives, Philadelphia

Within a month of Sandy Point State park’s opening, lawyers from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) sued the State of Maryland in Federal District Court arguing that the park’s beaches were unequal and should be integrated. The initial lawsuit failed, but a second lawsuit, led by Tucker Dearing, Linwood Koger, Jr., Juanita Mitchell, Robert L. Carter, Jack Greenberg and Thurgood Marshall, proved successful. In March 1955, the Appellate Court of the Fourth Circuit ruled in favor of the NAACP in Lonesome vs. Maxwell. The State of Maryland appealed to the Supreme Court, which refused to hear the case, upholding the Appeals Court ruling that segregated public beaches and bathhouses were unconstitutional.

On Memorial Day Weekend 1956, Sandy Point opened as an integrated park. Sandy Point went on to become one of Maryland’s most popular state parks. The legal case at Sandy Point, combined with a similar case at Fort Smallwood County Park, paved the way toward ending segregation in public parks and beaches across the nation.

Exploring the Sandy Point’s History

At present, Sandy Point State Park includes waysides on the Sandy Point Shoal Light Station, the War of 1812 and the U.S. Civil War. New waysides that will discuss the park’s early segregation period are forthcoming. The park’s expanded visitor center, which is presently in the planning stage, will include additional exhibits that will tell the park’s segregation story.

For Further Reading…

- “Sandy Point Farm House,” National Register of Historic Places Application, Maryland Historical Trust, 1971.

- “Sandy Point State Park,” Maryland Inventory of Historic Place, Maryland Historical Trust, 2003.

- R. Ross Holland, Jr. Maryland Lighthouses of the Chesapeake Bay : An Illustrated History, Maryland Historical Trust Press, 1997.

- William E. O’Brien, Landscapes of Exclusion: State Parks and Jim Crow in the American South, University of Massachusetts Press, 2016.

- Helen C. Rountree, Wayne E. Clark and Kent Mountford, John Smith’s Chesapeake Voyages 1607-1609, University of Virginia Press, 2007.