History of the Maryland DNR Forest Service Wildfire Program

With a salary of $1500.00 a year, a budget of $2000.00, and a staff of three assistant foresters and a secretary, Besley set out to undo centuries of poor land practices and spread the message of the new science of forestry with an almost religious fervor.

With a salary of $1500.00 a year, a budget of $2000.00, and a staff of three assistant foresters and a secretary, Besley set out to undo centuries of poor land practices and spread the message of the new science of forestry with an almost religious fervor.

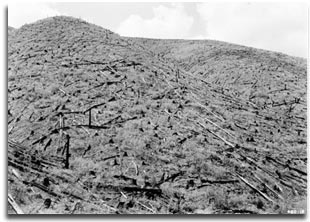

Along with teaching Marylanders the value of practicing sound forest

management techniques, Besley knew that preventing forest fires was an equally

important conservation practice. Decades of poor logging practices and

indiscriminate burning of the forest left poor soils, erosion, and large

uncontrolled fires that threatened life, property, and the natural ecosystem.

One of Besley’s first tasks was to create a network of volunteer Forest Wardens

to educate and enforce Maryland’s new forest fire protection laws.

Maryland's First Fire Wardens

Besley’s continuous travels around the state to prepare a comprehensive forest inventory (the first such study produced by any state in the U.S.) put him in contact with prominent local community leaders. It was these men to whom Besley appealed to their civic duty and recommended their names to the Governor to be commissioned as Forest Wardens.

Besley’s continuous travels around the state to prepare a comprehensive forest inventory (the first such study produced by any state in the U.S.) put him in contact with prominent local community leaders. It was these men to whom Besley appealed to their civic duty and recommended their names to the Governor to be commissioned as Forest Wardens.

With the 1910 Forestry Act, the law was amended to give wardens the powers of

constables so far as arresting and prosecuting persons for all violations of any

of the forest laws or of the laws, rules, or regulations enacted or to be

enacted for the protection of the State forestry reservations. Soon 300 such

dedicated citizens were appointed as Forest Wardens statewide.

Maryland’s first Forestry Act also provided the Forest Wardens compensation of $20.00 per year for services rendered and expenses incurred during the execution of their duties. In addition, for actual fighting of forest fires each Forest Warden received $1.50 for five hours or less and 25 cents per hour thereafter.

The Forestry Act instituted duties of the Warden that remain today. When a

Warden learns of a fire, he shall immediately go to the fire and employ such

persons and means in his judgment expedient and necessary to extinguish the

fire. The Act also authorized Forest Wardens “ To summon male inhabitants of the

county between the ages of 18 and 50 years to assist in extinguishing fires, and

may also require the use of horses and other property needed for such purpose.

Any person so summoned who is physically able, who refuses or neglects to

assist, or to allow the use of horses, wagons, or other material required, shall

be liable to a penalty of ten dollars.”

The Forestry Act instituted duties of the Warden that remain today. When a

Warden learns of a fire, he shall immediately go to the fire and employ such

persons and means in his judgment expedient and necessary to extinguish the

fire. The Act also authorized Forest Wardens “ To summon male inhabitants of the

county between the ages of 18 and 50 years to assist in extinguishing fires, and

may also require the use of horses and other property needed for such purpose.

Any person so summoned who is physically able, who refuses or neglects to

assist, or to allow the use of horses, wagons, or other material required, shall

be liable to a penalty of ten dollars.”

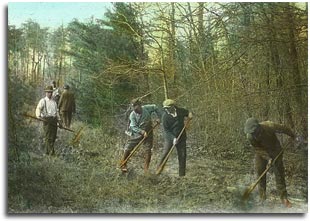

Local wardens were encouraged to draft their volunteers in

advance of the fire season to have a crew they knew and could count on when a

fire occurred. A 1943 Forest Warden Manual notes, “It should be remembered,

however, that men picked up at random by a Warden may very well be of doubtful

value on a forest fire.” Skilled men who were no strangers to hard work or

previous fire experience were preferred. “A man with such experience, or with a

stake in the outcome, is worth ten indifferent greenhorns.”

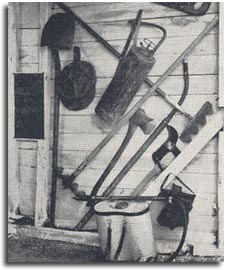

The Fightinest Tool…

Armed only with a badge issued by the Forest Department, early Forest Wardens had to supply their own tools and equipment. State Forester Besley advised the wardens, “The best tools with which to fight fire are the rake, hoe, shovel, and axe.” Besley further noted that the warden’s best assets were experience, activity and resourcefulness.

Armed only with a badge issued by the Forest Department, early Forest Wardens had to supply their own tools and equipment. State Forester Besley advised the wardens, “The best tools with which to fight fire are the rake, hoe, shovel, and axe.” Besley further noted that the warden’s best assets were experience, activity and resourcefulness.

Pine branches and wet grain sacks were soon discovered to be effective

firefighting implements. One Cecil County account notes that a moonshine bucket

used with a wooden pole and a swab of wet rags was well known in the region as

an effective extinguisher. In the early 1920’s, the Rich rake and knapsack pump

were standard equipment for the wardens. Fashioned from sickle-bar mower teeth

riveted to a piece of angle iron attached to a wooden handle, the rake proved to

be the warden’s “fightinest tool” that is used to this day. The knapsack pump

was a leaky forerunner to today’s bladder bag or backpack pump.

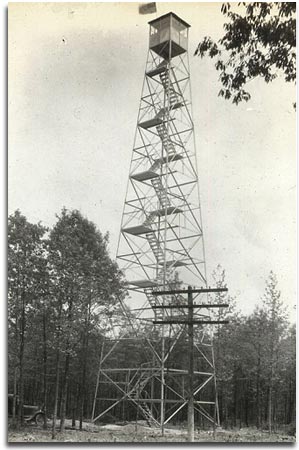

Maryland's Fire Towers

Of the 34 fire towers reported in use in 1943, it is assumed

the Civilian Conservation Corps constructed most of these towers in the early

1930’s, a time when the CCC began many conservation and civil engineering

projects that remain to this day. The first recorded fires tower in Maryland was

constructed in Bittinger, Garrett County in 1915, and was probably made of wood.

The Aeromotor Company of Broken Arrow, Oklahoma built nearly all of

Maryland’s fire towers, including those remaining today. Although they had many

designs, all of Maryland’s towers and most of those used in the southeast U.S.

were 80’ to 100’ feet tall and featured a 7’ by 7’ cab. The fire tower kits were

shipped from Chicago and when Aeromotor first started selling them in 1916, and

cost between $400.00 and $800.00. The Aeromotor Company, founded in 1888, is

best known throughout the Midwest and western U.S. as a manufacturer of

windmills and oil derricks (the steel tower structures are nearly identical),

and sells them to this day. The company was bought by a group of Texans in 1986

and relocated to San Angelo, Texas. Pictured here is one of the fire towers built by The Aeromotor Company

of Broken Arrow, Oklahoma. They built nearly all of Maryland’s fire

towers, including those remaining today.

The Aeromotor Company of Broken Arrow, Oklahoma built nearly all of

Maryland’s fire towers, including those remaining today. Although they had many

designs, all of Maryland’s towers and most of those used in the southeast U.S.

were 80’ to 100’ feet tall and featured a 7’ by 7’ cab. The fire tower kits were

shipped from Chicago and when Aeromotor first started selling them in 1916, and

cost between $400.00 and $800.00. The Aeromotor Company, founded in 1888, is

best known throughout the Midwest and western U.S. as a manufacturer of

windmills and oil derricks (the steel tower structures are nearly identical),

and sells them to this day. The company was bought by a group of Texans in 1986

and relocated to San Angelo, Texas. Pictured here is one of the fire towers built by The Aeromotor Company

of Broken Arrow, Oklahoma. They built nearly all of Maryland’s fire

towers, including those remaining today.

Tower operators were often local women who lived in the area, who provided a

watchful eye during times of high fire danger for a salary of $100.00 a month.

The 150 tower steps or occasional thunderstorms didn’t faze Cub Hill tower

operator Mrs. Mohan. In a 1947 Baltimore Sun article, Mrs. Mohan reported her

biggest worry were the curious pilots from nearby airfields. “Many of the boys

from one of the county airfields fly around the tower, looking at me working.”

She explained. “I don’t mind that, but one day they might misjudge their

distance and hit the tower.”

As Maryland became more populated, and communication systems such as 911 came

into being, fire towers became obsolete in many of the once-rural areas they

protected. Many were dismantled in the 1950’s and 1960’s, although a few remain

available for use throughout the state. Most of the remaining fire towers now

serve as part of the DNR radio communication network with radio antenna attached

to the tower.

The Smoke Chasers...

By 1935 the Forest Warden ranks had swelled to 650 men. As the

network of Forest Wardens and fire towers increased across Maryland, so did the

need to have more people “on the ground” to assist wardens in their firefighting

duties. In the late 1920’s, the position of Forest Guard, or “Smokechaser” was

developed. After a tower operator spotted a “smoke”, a Smokechaser living nearby

would be dispatched to investigate.

In a 1928 letter to prospective Smokechasers, Assistant Forester John Curry

wrote: “Whenever smoke is sighted from the tower, you should leave immediately

for the fire. Do not wait until the smoke develops and do not wait until a call

has been made to the Forest Warden – go immediately…It is necessary for you to

get away quickly. Have your tools ready in your machine. Fill your spray tank in

advance. Have your torch ready for action. Keep your car headed toward the way

out, and when the call comes, make time.”

Smokechasers had to be resourceful as well. In the absence of fire towers, a

tall tree served as a capable lookout. In his recollection of smokechasing in

the 1930’s, Smokechaser Herman Toms of Frederick County noted a typical day: “I

worked mostly in Washington County, Red Hill section Southeast of Keedysville

climbing a tree for a lookout with a crank type telephone nailed to a tree with

a box with a lock on it. I usually climbed that tree about every 30 minutes or

so and staying in the tree for long periods of time when the danger was high.”

The Mechanical Age…

It was not until the 1940’s that the Department of Forest and Parks developed mobile fire fighting units. A fleet of nine 1 ½ ton trucks, each with 275 gallons of water, several hundred feet of hose and hand tools for a 20 person crew allowed wardens to get to fires quicker and put more water on the blaze. The Panama fan belt-driven model was the fire pump of choice.

“You’ve got to mechanize today to fight forest fires under modern conditions.” Said H.C. Buckingham, Maryland’s third State Forester. “People just won’t work with their hands the way they used to; they demand tools and equipment.” By 1956, Buckingham’s Forest Service boasted 185 two-way radio sets, 34 lookout towers, 10 tractors with fire plows, 18 portable pumps on light vehicles, and a fleet of 22 specially equipped jeeps.

Early tractor plow units (such as pictured above) provided little protection

for the dozer operator from falling snags and brush when plowing firelines. By the 1960 units were improved with roll over protection cages and wire mesh screen to protect the operator.

Fire Management today

Although only a few fire towers remain today that remind us of the humble beginnings of the wildfire protection program in Maryland, the proud heritage of protecting our forest from the devastating effects of wildfire is still carried on by the men and women of the DNR Forest Service. As in 1906, careless people start the majority of wildfires in Maryland. The leading causes of wildfire in Maryland are debris burning, arson, and children.

Although only a few fire towers remain today that remind us of the humble beginnings of the wildfire protection program in Maryland, the proud heritage of protecting our forest from the devastating effects of wildfire is still carried on by the men and women of the DNR Forest Service. As in 1906, careless people start the majority of wildfires in Maryland. The leading causes of wildfire in Maryland are debris burning, arson, and children.

Our earliest Forest Wardens would be impressed, although a bit bewildered at

the strides that the fire management program has taken. Fire weather is

monitored from remote automated weather stations that data can be accessed from

the Internet and software helps predict expected fire behavior. Fires are

reported and dispatched through enhanced communication systems; and fire

perimeters are plotted using Global Positioning Satellites. Great strides have

been made in modern well-equipped wildfire engines with the latest technology

such a Class A foam delivery systems to extinguish wildfires faster and prevent

flare ups. Tractor plow units that provide an effective initial attack

capability and provide the dozer operator with protection within an enclosed

cab.

What has changed is our knowledge and use of fire as a management tool, and the understanding that not all fires are bad. Prescribed fires applied under the proper weather conditions by professional firefighters can have beneficial effects on the environment by creating wildlife habitat, preparing forest harvest areas for replanting, and hazard fuel reduction by reducing fuel loading.

What hasn’t changed is the dedication and purpose of the Maryland DNR Forest

Service wildland firefighters, who look back on this rich heritage of

“smokechasing” as the very heart of the wildfire management program. Today, the

agency is equipped with the training and specialized equipment needed to meet

the challenges and demands to provide effective wildfire protection services for

the citizens and communities of Maryland. These resources are also made

available to other states and federal agencies. Highly trained wildland fire

crews and single resource experts have traveled across the United States to

battle some of the nation’s toughest wildfires. Nearly a century later, we think

Mr. Besley would be proud!

Photographs (top to bottom):

- Hillsides cleared of trees during the early

1900's

- Some of the State's first Forest Wardens

- Putting out fires with rakes and shovels

- Hand tools used in 1928

- One of the fire towers built by The Aeromotor Company of Broken Arrow, Oklahoma.

- Early tractor plow unit

-

Present day fire truck (2006)

Authors:

- Will Williams, Educations Specialist, Maryland DNR Forest Service (ret.)

- Monte Mitchell, State Fire Supervisor, Maryland DNR Forest Service

Bibliography

- Curry, John R. Letter to Smokechasers. State Department of Forestry,

Baltimore, MD. 4 April 1923

- Fielding, Geoffrey W. “Smoke Get in Their Eyes.” Baltimore Sun, 3 Aug. 1947,

Sec. A, Pg. 3

- Kaylor, Joseph F. “Manual for Forest Fire Wardens” Department of Forests and

Parks, Baltimore, MD. 1943, pp.28-29

- Overington, Helen Besley. Personal interview. 13 May 2004

- Toms, Herman. Personal recollections. Date unknown

- Warren, Edna. “Forests and Parks in the Old Line State.” American Forests,

Oct. 1956, pp. 13-26