Maryland Forestry — 1942-1977

Maryland Forestry — 1942-1977

Address by James Mallow,

Retired Maryland State Forester,

for the Maryland Forests Association 2005 Annual Meeting,

Rocky Gap Lodge & Resort, November 2005.

I’d like to begin on a personal note. Without a doubt it is an honor and a

distinct pleasure to be among so many friends; some whom I have known for quite

a long time. There is not a day goes by down there in South Carolina that I

don’t think of my friends and colleagues from throughout my career in forestry

and parks and the associations I enjoyed with fellow members of MFA. I will

forever hold dear the fond memories of the paths we traveled, the discussions

and debates we had and the battles for natural resources we won and lost. Thanks

for the memories.

In terms of today’s presentation I want to thank Jack Perdue, Robert Bailey,

state park historian, Tunis Lyon and former Forest Service Ranger Will Williams

for providing me with the volumes of documentation I reviewed and utilized to

prepare my remarks.

In terms of today’s presentation I want to thank Jack Perdue, Robert Bailey,

state park historian, Tunis Lyon and former Forest Service Ranger Will Williams

for providing me with the volumes of documentation I reviewed and utilized to

prepare my remarks.

When I was contacted to see if I would take part in this meeting if thought,

“Great, I must have achieved something as a State Forester because they want me

here to impart some wisdom, etc”. Well, that was a good feeling until I realized

that most of the rest of the state foresters were either dead or not able to

attend!

Anyway, the issue at hand is to share with you some thoughts, perspectives and

some personal insights about the business of forestry in Maryland between 1942

and 1977.

If this talk were on the internet, the key words you might look for to get a

feel for the dominant influences affecting the history of forestry in Maryland

during this period they would be: personalities, science, politics, government

priorities, 800 pound gorillas, growth, urbanization and relevancy.

Because I truly believe that any organization is, to a large extent, determined

by the make-up, background and values of the leaders of that organization I am

compelled to begin my time with you talking about the three state foresters who

occupied that position between 1942 and 1977.

Joe Kaylor became Maryland’s second state forester in June of 1942 after Fred W.

Besley reached the mandatory retirement age of 70. Now, after listening to

“Champ” tell us about Mr. Besley we all know what big, big shoes Mr. Kaylor had

to fill; but, I believe, that history proved that Mr. Kaylor was up to the task.

Most importantly, he seemed to shared Besley’s vision and passion for the future

of forestry in the old line state. The first thing Joe had to do, however,

didn’t have anything with forestry but nevertheless needed to be done. He had to

make certain that forests and parks transitioned into a new organization. In

1941, just one year before he took over, an organizational change had taken

place that moved the state department of forestry, which had been under the

University of Maryland, to the Maryland Board of Natural Resources.

Joe Kaylor became Maryland’s second state forester in June of 1942 after Fred W.

Besley reached the mandatory retirement age of 70. Now, after listening to

“Champ” tell us about Mr. Besley we all know what big, big shoes Mr. Kaylor had

to fill; but, I believe, that history proved that Mr. Kaylor was up to the task.

Most importantly, he seemed to shared Besley’s vision and passion for the future

of forestry in the old line state. The first thing Joe had to do, however,

didn’t have anything with forestry but nevertheless needed to be done. He had to

make certain that forests and parks transitioned into a new organization. In

1941, just one year before he took over, an organizational change had taken

place that moved the state department of forestry, which had been under the

University of Maryland, to the Maryland Board of Natural Resources.

This Board consisted of the Tidewater Fisheries, Game and Inland Fish, State

Forests and Parks, Geology, Mines and Water Resources and a Research and

Education division. The various groups within this Board, including Forests and

Parks, maintained a great deal of autonomy and this was, in fact, according to

some, a better arrangement than when Forestry was under the University of

Maryland. The Board of Natural Resources lasted until 1969 when the Department

of Natural Resources was created.

K

aylor was a product of Pennsylvania state forest academy (now Penn State-Mont

Alto). Historical notes from early forest service training sessions mention that

he was “a good politician (with) lots of personality”.

The fact that historical literature recognized Kaylor as a “good politician” is

perhaps the first indication that between Besley’s time (when Besley was assured

that “he would be free to discharge his duties as state forester without

political interference”) and Kaylor’s reign there appeared to be a change of

heart by politicians related to the management of natural resources - a change,

that in my opinion, has prevailed over the years and one that has became more

intrusive and, for the most part, had a detrimental effect on the Forest

Service’s ability to manage Maryland’s forests.

The fact that historical literature recognized Kaylor as a “good politician” is

perhaps the first indication that between Besley’s time (when Besley was assured

that “he would be free to discharge his duties as state forester without

political interference”) and Kaylor’s reign there appeared to be a change of

heart by politicians related to the management of natural resources - a change,

that in my opinion, has prevailed over the years and one that has became more

intrusive and, for the most part, had a detrimental effect on the Forest

Service’s ability to manage Maryland’s forests.

Anyway, Mr. Kaylor started his tenure as state forester with a bang by

overseeing the development of the first comprehensive public regulation of

forest practices on private lands east of the Mississippi river. The forest

conservancy district act of 1943 was a piece of landmark legislation that to

this day is front and center of regulations and law that govern the conservation

and management of Maryland’s forest resources.

The act has as its objectives (1) the encouragement of private woodland owners

to manage their woods through scientific management (2) promotion of soil

erosion and flood control through reforestation and (3) fulfillment of the

state’s right and obligation to exercise regulatory powers designed to eliminate

destructive forest practices.

Finally, as most of us are aware, the act advocated local control of the

oversight of these objectives by the creation of district forestry boards. A

tribute to Mr. Kaylor’s vision is the fact that these volunteer boards serve the

forestry community to this day.

Another major contribution was his recognition of the importance and

relationship between forests and the watershed scale of those forests. Probably

his experiences with the Tennessee Valley Authority, prior to his arrival in

Maryland, served as the training ground for his watershed management

accomplishments at the helm of Maryland forestry.

For example, in a 1957 article in the Department’s newsletter, The Old Line

Acorn, Kaylor noted “the Department has the first try at saving, increasing, or

improving both the quantity and quality of our water supplies, since watershed

improvement is primarily a forestry issue”. This effort sounds very much, to me,

like today’s emphasis on watershed restoration projects such as riparian

buffers.

For example, in a 1957 article in the Department’s newsletter, The Old Line

Acorn, Kaylor noted “the Department has the first try at saving, increasing, or

improving both the quantity and quality of our water supplies, since watershed

improvement is primarily a forestry issue”. This effort sounds very much, to me,

like today’s emphasis on watershed restoration projects such as riparian

buffers.

Just think, before the minions in Maryland advocating for Bay restoration ever

existed, including groups such as the Chesapeake Bay Foundation and the Critical

Area Commission, Maryland forestry was leading the way. Isn’t it a shame that

over the years forestry seems to have lost some of that leadership role

regarding the role of forests in the sustainability of clean water.

Steve Koehn’s oft spoken phrase “forests are the solution to water pollution”

needs to get more press time.

Finally, Joe Kaylor, following the lead of Governor McKeldin, placed a new

emphasis on the State’s role in outdoor recreation by expanding efforts to

acquire and develop land for public parks.

Primary emphasis was placed on the development of parks along stream valleys

such as Patapsco, Seneca Creek and Gunpowder. The expansion of these type park

areas certainly resulted in new park areas, but at the same time, continued the

emphasis on watershed protection which is a prime example of multiple use

management. The final major action put in place by the Kaylor reign as State

Forester was the passage of Maryland’s tree expert law in 1945.

Once again, he demonstrated a vision for the future of Maryland’s urban areas by

ensuring that this consumer protection law would guarantee that people who

offered themselves to the public as “tree experts” had, in fact, a demonstrated

knowledge and expertise to do tree care in a safe and scientifically accepted

manner.

Whe

n Joe Kaylor was promoted to director of forests and parks in 1947, after

having served as State Forester for five years, his Assistant State Forester H.

C. Buckingham was appointed State Forester.

Henry C. Buckingham became the State Forester in 1947 and served in that

capacity until 1968. “Double 0” as he was referred to because of his car radio

call letters was, like Kaylor, sensitive to the growing trend toward outdoor

recreation; and certainly sensitive to the desires of Governor McKeldin to

expand recreation in the state. However, “Buck’s” allegiance was always to the

forestry side of the organization.

Henry C. Buckingham became the State Forester in 1947 and served in that

capacity until 1968. “Double 0” as he was referred to because of his car radio

call letters was, like Kaylor, sensitive to the growing trend toward outdoor

recreation; and certainly sensitive to the desires of Governor McKeldin to

expand recreation in the state. However, “Buck’s” allegiance was always to the

forestry side of the organization.

Shortly after becoming State Forester he relocated the state forest tree nursery

from College Park, where it had been, to a site near BWI Airport, where it

remained until 1996 when Buckingham Forest Tree Nursery was replaced by Route

100 and moved to a three hundred tract of land near Preston, Md. Once located at

“Buckingham” Maryland forestry began tree improvement activities including the

establishment of seed tree orchards that remain today.

In a letter sent to me from Tunis Lyon he reported to me that during Buck’s time

fire control was the driving force in terms of priorities and when a forest fire

occurred everyone, including park people, roadside tree crews and everyone else

who could breath were on the scene. Such was the integration of the work force

at that time; which certainly seems to have gone by the wayside and has led to

an era when foresters and forest rangers and park managers, and park rangers,

and law enforcement officers and park maintenance too often are

compartmentalized into specific jobs where they have little or no interest or

awareness in what their colleagues are doing or how all the various missions fit

in the bigger picture.

In a letter sent to me from Tunis Lyon he reported to me that during Buck’s time

fire control was the driving force in terms of priorities and when a forest fire

occurred everyone, including park people, roadside tree crews and everyone else

who could breath were on the scene. Such was the integration of the work force

at that time; which certainly seems to have gone by the wayside and has led to

an era when foresters and forest rangers and park managers, and park rangers,

and law enforcement officers and park maintenance too often are

compartmentalized into specific jobs where they have little or no interest or

awareness in what their colleagues are doing or how all the various missions fit

in the bigger picture.

One of the lasting fire control mechanisms put in place by Buckingham in 1954

was the passage of the Mid-Atlantic Forest Fire Protection Compact that made it

possible for the states of Maryland, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, West

Virginia and Virginia to share fire resources and to allow for inter-state

movement of resources to aid states in need.

As I have said before, during McKeldin’s governorship and his successor, J.

Millard Tawes, there was an ever increasing emphasis on recreation in the state.

This effort resulted in the creation of some “park specific” organizational

changes in the forests and parks by the naming of a Superintendent of State

Parks in 1954 to serve on a parallel authority as the State Forester.

Ultimately, when Joe Kaylor retired as director in 1964 a “non-forester” was

appointed as its director. Spencer P. Ellis led the park development movement

including the creation of numerous state parks and the creation of a law in 1969

that allowed for a portion of the state’s real estate transfer tax to be

dedicated to the purchase of open space land for parks.

During this time the forestry side of the department continued on its

own—serving private forestland owners and managing the State Forests. The

current Forest Conservation and Management Act (FCMA) of 1957 provided the

opportunity for Buckingham and his staff to improve their delivery of forestry

to landowners by providing incentives that resulted from the act to landowners

who were actively managing their forest land.

During this time the forestry side of the department continued on its

own—serving private forestland owners and managing the State Forests. The

current Forest Conservation and Management Act (FCMA) of 1957 provided the

opportunity for Buckingham and his staff to improve their delivery of forestry

to landowners by providing incentives that resulted from the act to landowners

who were actively managing their forest land.

In Maryland, beginning in 1960, the beginning of the urban development era of

the state and the environmental movement would have a profound impact on the

forest resources of the state and how business was conducted by the forestry

organization; and definitely impacted the tenure of Mr. Buckingham and his

Maryland Forest Service.

As an integral outcome of this emerging awareness, the 1960 creation of the

Department of Chesapeake Bay Affairs represented Maryland’s first official

recognition of the need to “Clean Up the Bay”.

Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring, published in 1962, served to rally folks

around an emerging environmental movement and within two years, between 1962 and

1964, the Baltimore beltway, the Washington beltway and the I-95 corridor

between them came on line. Of course, all of the roads and the expanding urban

growth and population expansion that followed changed forever the landscape of

Maryland and the way natural resources, including public and private forests,

were viewed.

So it was, then, that the last half of H. C. Buckingham’s 21 years as State

Forester was served within the context of the urbanization of Maryland with the

resulting growth of laws and regulations that began to impact land use, the

beginning of the massive loss of forestland to emerging development and the

changing pattern of private forest landowners across the State.

A.R. “Pete” Bond came up through the ranks of the Forest Service and stepped

into the State Forester’s role in 1968 upon the retirement of Mr. Buckingham.

“Pete” had joined the Forest Service out of Penn State’s Forestry School; and in

spite of a somewhat suspect academic training (just kidding) he served the

Forest Service with distinction. His 9 years as State Forester were filled with

examples of his visionary outlook on the need to have the citizens of our state

understand what forestry was about as well as the benefits the entire state

enjoyed as a result of well managed and protected forests.

A.R. “Pete” Bond came up through the ranks of the Forest Service and stepped

into the State Forester’s role in 1968 upon the retirement of Mr. Buckingham.

“Pete” had joined the Forest Service out of Penn State’s Forestry School; and in

spite of a somewhat suspect academic training (just kidding) he served the

Forest Service with distinction. His 9 years as State Forester were filled with

examples of his visionary outlook on the need to have the citizens of our state

understand what forestry was about as well as the benefits the entire state

enjoyed as a result of well managed and protected forests.

As we have seen so far in Champ’s (Francis "Champ" Zumbrun) talk and in mine, throughout the 100 year

history of forestry in Maryland, the state organization responsible for the

protection and management of the state’s forest resources went through many

organizational changes and was housed under an assortment of Departments and

Boards. Our history of forestry cannot be fully understood without talking about

those parent organizations and their influences.

So, it was when Mr. Bond came on the scene as State Forester in 1968.

It was just one year later, in 1969, that state government completely

reorganized and got rid of hundred’s of various boards and commissions and

replaced them with a cabinet form of state government. The Forest and Park

Service, as well as many of their companion Departments of Fisheries and

Wildlife and Water Resources, was placed in the newly formed Department of

Natural Resources. Then Governor Marvin Mandel called upon former Governor J.

Millard Tawes to serve as the first Secretary. Some of you in the audience may

have wondered how the present DNR building in Annapolis came to be named the

Tawes office building—now you know, if you didn’t already!

Anyway, this creation of DNR was, by far, the biggest most far-reaching effort

ever undertaken to restructure Maryland’s government. The creation of this, what

I affectionately call, the 800-pound gorilla would forever change the dynamics

of the workings of the state’s natural resources organizations.

Pete Bond assisted the Forest and Park Director in the transition of the

organization into the DNR, at the same time making every effort to get the

service ready to deal with the forest resources of the state in an ever-changing

landscape. During Pete’s time as State Forester the first Wildlands area was

designated, as the Big Savage Area in Garrett County was set aside from active

management. As most of you know, this land use designation now exists on nearly

45 thousand acres of state forest land.

Pete Bond assisted the Forest and Park Director in the transition of the

organization into the DNR, at the same time making every effort to get the

service ready to deal with the forest resources of the state in an ever-changing

landscape. During Pete’s time as State Forester the first Wildlands area was

designated, as the Big Savage Area in Garrett County was set aside from active

management. As most of you know, this land use designation now exists on nearly

45 thousand acres of state forest land.

The first Earth Day was celebrated in 1970 to highlight and raise awareness of

the environmental movement in the U.S. and the recognition that perhaps we, as a

nation, should value our renewable natural resources with a fresh vision. This

celebration, over the years, has afforded Forestry the opportunity to tell their

story; and Pete Bond was in the forefront of developing such educational

programs for the Maryland Forest Service.

The Board of Licensing for Foresters was established in 1972 and to this day

provides forest landowners with the protection of assurance that only Foresters

registered with the Board can practice their craft in the State.

One year prior to Pete’s retirement in 1977, the Maryland Forests Association

(MFA) was incorporated. I know that all of you in this room celebrate the

beginning of this organization and the magnificent leadership role it has

occupied over these many years. I believe it is fitting and proper for this MFA

meeting to be the venue were we launch the 100th year celebration of forestry in

Maryland.

Tunis Lyon shared with me what was probably the defining statement regarding

Pete Bond’s legacy to forestry when he said “Pete was great about educating the

foresters when new information came along. He was always ready, willing and able

to tell us about new material.” Pete truly believed that education was the key

to understanding what forestry was all about; whether that education was

directed at his foresters or to the public. Mr. Bond retired in 1977.

As I begin to wrap up my part of the program here today I would like to quickly

go back to the beginning when I suggested that if we were dealing with key words

as on the internet the following would define the 1942 to 1977 years of forestry

in Maryland.

Personalities, science, politics, government priorities, 800-pound gorillas,

growth, urbanization and relevancy were the words. Mostly I’ve talked about the

personalities of the state foresters and how growth and urbanization began to

alter the landscape and impact the forest resources of our state.

The organization that has had the most impact on forestry is that 800-pound

gorilla, the DNR; and a quick look at DNR is, I believe, warranted. J. Millard

Tawes was replaced by Mr. James Coulter. Mr. Coulter, who passed away very

recently, was a scientist first and foremost and he didn’t really like the

politics. He dealt with the natural resource issues of his time and allowed his

staff and division heads to practice their scientific craft and expected them to

tell him what the science of an issue demanded. If the politics of an issue

required consideration it took place after the all important scientific

discussions had taken place.

In my opinion, having served five Secretaries of Natural Resources, I believe

that the Department walked the tallest and had the greatest impact on the

management of the State’s natural resources when its leadership was permitted to

practice their scientific crafts and provide sound advice to the Governor and

the State Legislature. I will forever be convinced that the citizens of the

state had a greater trust for the Department and supported their actions much

more when it was looked at as a source of sound scientific management instead of

as a political pawn serving at the whim of the political wind of the day.

Fortunately, for the citizens of Maryland scientists like Mr. Coulter and Dr.

Sarah Taylor-Rogers were effective at advancing the scientific agenda’s of the

agency for the overall betterment of the State’s natural resources. My sources

also tell me that the present leadership of DNR including Secretary Franks and

Assistant Secretary Mike Slattery have made it known inside and outside the

Department that the science of issues are of paramount importance in determining

the direction of the agency. I would personally like to commend the Secretary

for bringing the management and operation of the state forests back under the

leadership of the Forest Service. A lot of us fought to have that happen and

we’re glad it finally has.

It has been difficult, over time, for the Department to compete for resources

with the big agencies in State government who constantly have the ear of the

people and the legislature. Maintaining some degree of relevance amid all of

that posturing has been difficult to say the least.

When I look back over the 35 years I have been talking about I come to the

conclusion that a lot of what happened then is still, to some degree, continuing

today; and perhaps that fact alone is why we should look at the past as a

prologue to the future.

When you look across Maryland’s landscape today, the need to sustain forests as

a viable land use is still a critical matter amid the deforestation to other

land uses and resulting development that is taking place.

I submit to you that with proper stewardship by private forest land owners who

are provided with the proper incentives to do what is right for their woods it

is still a valid approach to maintaining the forest land base in the state.

Policy makers are more aware than ever of the role that forest land can play as

a hedge against uncontrolled development. Just as important, these policy makers

are more aware to equate the reality that owners of this forest land must

somehow be able to realize an economic viability for their property in order to

retain it as forest land.

The public debate regarding economics versus environmental protection continues

as we constantly hear from people who think that harvesting trees will destroy

our environment on the one hand, or on the other hand, that protecting the

environment too vigorously will destroy the economy. The vision of sustainable

forest management says that not only is it possible for economic values and

environmental values to both be supported through forest management, but that it

is essential that these two values work together

.

Back in the Kaylor days the relationship between forest cover on the land and

the quality of our water was a “white hat” issue for forestry; and that should

be no different today. We all know that water quality is directly related to the

condition of the land that it travels across on its way to the water courses of

the landscape. The problems of poor water quality that result from agricultural

runoff and stormwater runoff from development activity and impervious surfaces

is even more relevant an issue today than in the past. It costs a lot of money

to rectify these runoff issues; whereas, in large measure, these problems could

be avoided in the first place if sufficient effort and financial resources were

devoted to preventive measures.

Back in the Kaylor days the relationship between forest cover on the land and

the quality of our water was a “white hat” issue for forestry; and that should

be no different today. We all know that water quality is directly related to the

condition of the land that it travels across on its way to the water courses of

the landscape. The problems of poor water quality that result from agricultural

runoff and stormwater runoff from development activity and impervious surfaces

is even more relevant an issue today than in the past. It costs a lot of money

to rectify these runoff issues; whereas, in large measure, these problems could

be avoided in the first place if sufficient effort and financial resources were

devoted to preventive measures.

So, as I look at it, things have not changed. The players are different to be

sure and the issues bigger in terms of magnitude; but the bottom line remains

the same. The roles that Forestry have been and will continue to be called upon

to assume remain a challenge and an opportunity to make a positive mark across

the Maryland landscape. As a part of this 100 year movement of forestry we all

have an obligation to carry on the vision and the commitments of the past into a

future full of possibilities.

Steve Koehn’s oft spoken phrase “forests are the solution to water pollution”

needs to get more press time. - Jim Mallow

Acknowledgements:

Address by James Mallow, Retired Maryland State Forester, for the

Maryland Forests Association 2005 Annual Meeting, Rocky Gap Lodge & Resort,

November 2005

In 1995 Jim Mallow became State Forester and during his six years at the

helm he skillfully guided the agency once again into a leadership role regarding

the importance of trees and forests as they can contribute to the Chesapeake Bay

restoration effort. It was on Jim's watch (1995-2001) that the Riparian Forest Buffer

Initiative, the first CREP in the nation and the Potomac Watershed Partnership

were established to restore streamside forests to filter out sediments and

nutrients before getting into the waters of the Bay. Jim was also

instrumental in the establishment of an urban forestry program within the University of Maryland's College of Agriculture and

Natural Resources

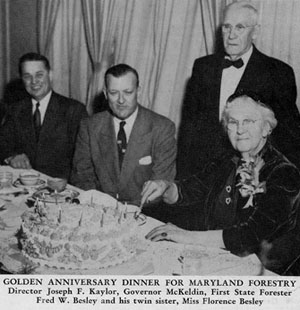

Photographs (top to bottom):

- Left to right: Unknown, Joe Kaylor, Henry C. Buckingham and A. R. "Pete"

Bond, photograph by M.E. Warren.

- Meeting of American Foresters Association,

LaPlata, 1956. Note Joe Kaylor, A.R. "Pete" Bond and Henry C. Buckingham

attended.

- 50th Anniversary of the Maryland State

Forest Service: (l to r: State Forester Joe Kaylor, Governor McKeldin, first

State Forester Fred. W. Besley and his twin sister, Florence Besley.

- Family Forest Field Day, Phoenix, Md.

1962. State Forester Joe Kaylor pictured on far right.

- Maryland State Fire

Wardens, 1947. Man in lower right corner is A.R. "Pete Bond.

- Garrett

Forestry Field Day - James Mallow is on the far left

and State Forester H.C. Buckingham is third from the left. Date of photo and other participants unknown.

- Former Maryland State

Comptroller Louis Goldstein and H.C. Buckingham at Tree Farm dedication

- A.R. "Pete" Bond

(right) in tobacco barn.

- Executive Committee, Forestry Board Association

with Director Ellis, Arbor Day Proclamation: Governor's office:

(L-R) Full, Rodgers. Ellis, Mizell, Druden and A.R. "Pete" Bond.

- Potomac

State Forest in Garrett County