By Vaughn Deckret

How Fred W. Besley, Maryland's first state forester, became an outstanding environmental leader has much to do

with the man who inspired him-Gifford Pinchot.

Gifford Pinchot was an extraordinary man. Born to wealth and a family of culture and

connections, he chose to forgo the path of business, so successfully followed by

his father and grandfathers, to blaze new trails. On graduating from Yale in

1889, he could have pursued any profession on earth, yet Gifford Pinchot decided

to become a forester.

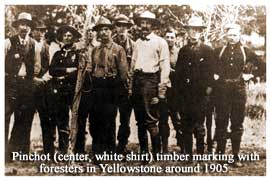

This remarkable decision had far-reaching consequences. In

the early 1890s, Pinchot (PIN-show) became the nation's first practicing

forester. In 1898, he began his 12-year career as chief of what became the U.S.

Forest Service. In 1900, he founded the Yale School of Forestry and the Society

of American Foresters.

This remarkable decision had far-reaching consequences. In

the early 1890s, Pinchot (PIN-show) became the nation's first practicing

forester. In 1898, he began his 12-year career as chief of what became the U.S.

Forest Service. In 1900, he founded the Yale School of Forestry and the Society

of American Foresters.

For bringing the profession to America and promoting the

new field relentlessly throughout his life, he is recognized as the father of

American forestry. Pioneering forestry, though, proved to be the prelude to even

greater deeds: formulating the idea of conservation as we now understand the

term and launching the conservation movement.

Spirit of the Times

Many easily

forget the degree to which natural resources were taken for granted after

Europeans colonized America. The forests were so vast, the game so plentiful,

and the bays and rivers so packed with fish and shellfish that seizing what was

wanted without a thought to future supply became a countrywide habit.

At the end

of the 1800s, settlers out West were still piling and burning saw logs just to

get rid of them. The eastern hemlock was approaching extinction as the trees

were being methodically stripped of their bark, a prized source of tannin for

the leather-making industry.

Trees, much like the oysters in our Chesapeake Bay,

were seen as inexhaustible. To displace destructive use of forests with wise use

that guarantees sustainable supply was not simply a formidable task: It was an

idea alien to nearly everyone. In this time of wanton devastation, accelerated

by advances in machinery and transportation, Gifford Pinchot came of age.

Early

Influences

Pinchot's life's work had early beginnings. As a boy, he loved the

woods and everything about them. Camping, fishing and hunting were favorite

pastimes. He talked of becoming a naturalist when he grew up. His father often

spoke of forestry and liked to quote a French intellectual who said that

neglecting forests was "not merely a blunder, but a calamity and a curse." When

Pinchot was about to begin college, his father asked him to consider forestry as

a career.

George Marsh's "Man and Nature," a gift from his parents on his 21st

birthday, profoundly influenced young Pinchot. The book attributes the collapse

of various ancient Mediterranean settlements and civilizations to deforestation

of watersheds. The ensuing erosion of fertile soil and silting of waterways and

harbors eventually destroyed their economies and social orders. Thereafter,

Pinchot never doubted the direct relation of forests to a society's welfare.

Preparing for his Life's Work

Because no schools of forestry yet existed in

America, Pinchot traveled to

Europe, sought advice from several eminent

authorities on forestry, and then enrolled in the National School of Forestry in

Nancy, France. In addition to completing its one-year program, he visited

forests all over Europe, some of the most superbly managed on earth. Among them

was the Sihlwald, a stunningly productive forest near Zurich that had been

regularly managed long before Columbus sailed west.

Because no schools of forestry yet existed in

America, Pinchot traveled to

Europe, sought advice from several eminent

authorities on forestry, and then enrolled in the National School of Forestry in

Nancy, France. In addition to completing its one-year program, he visited

forests all over Europe, some of the most superbly managed on earth. Among them

was the Sihlwald, a stunningly productive forest near Zurich that had been

regularly managed long before Columbus sailed west.

In Europe, he acquired a

grounding in silviculture (knowledge of the care and cultivation of trees), the

economics of forestry, and forestry law. There he formed a concrete

understanding of the forest as a crop. On returning home in December 1890,

Pinchot wasted no time pursuing his priorities: establishing relations with

leaders of the nascent forestry movement, practicing forestry, and seeing

America's great forests.

Crucial Experience

His work in the woods began in early

1891, when Phelps Dodge hired him to evaluate timberlands in Pennsylvania. Soon

afterwards, he was invited to accompany the chief of the U.S. Division of

Forestry on a mission to examine hardwoods in Mississippi and Arkansas. That

spring, Phelps Dodge sent him to evaluate holdings in Arizona.

As the fledgling

forester wrote, this trip gave him a chance to "shake hands with the U.S.A."

Conducting his own "grand tour," he saw the Grand Canyon, Yosemite, the giant

sequoias of the Sierras, and the towering redwoods and Douglas firs of the

Pacific coastal forests. The vastness and magnificence of the largely unspoiled

West left him in awe and heightened his sense of what was at stake.

A flood of

practical experience followed. He was hired to manage forests on George

Vanderbilt's mammoth estate in North Carolina. In late 1893, he took on

additional work as a consulting forester, applying the science of forestry in

such places as the Adirondacks of New York and the pine and white cedar woods of

New Jersey.

Of crucial importance was his appointment to the National Forest

Commission, formed to write a plan for administering all forests on U.S. public

lands. In addition to the experience evaluating western forests that were to

become 21 million additional acres of national reserves, Pinchot got an

education in the realities of politics, legislation, bureaucracy, regional

interests and the power of public opinion. Another result was that two

presidents, Grover Cleveland and William McKinley, and numerous senators,

congressmen and high-level bureaucrats became well acquainted with the energetic

and able Gifford Pinchot.

Forest of Accomplishments

When Pinchot was appointed

chief of the U.S. Division of Forestry in 1898, he was given a free hand to act

as he saw fit. So began the transformation of an insignificant federal agency

into the motherland of American forestry and incubator of the conservation

movement.

To show that practical forestry pays off, Pinchot immediately offered

forestry services to private owners and other federal agencies. This approach

was both shrewd and necessary because, as odd as it sounds, his agency had no

control over federal forests, which covered millions of acres.

To show that practical forestry pays off, Pinchot immediately offered

forestry services to private owners and other federal agencies. This approach

was both shrewd and necessary because, as odd as it sounds, his agency had no

control over federal forests, which covered millions of acres.

Pinchot knew that

to advance forestry in giant steps required a highly capable organization, so he

built one. He steadily enlarged his staff (e.g., from 11 to 179 in three years)

and included respected professors to provide scientific expertise. He rejected

the political spoils system and hired only on merit. He also demanded

professionalism in all matters. For example, all inquiries from the public and

Congress had to be answered fully and quickly, and correspondence had to be

replied to within 36 hours.

His staff became renowned for its

esprit de corps,

and his agency was widely seen as the best run in the federal government. In the

words of Stewart Udall, Secretary of the Interior in the early 1960s, Pinchot

made the U.S. Forest Service "in his time the most exciting organization in

Washington."

Throughout his years in Washington, Pinchot energetically

cultivated political and public support for his agency's work and its mission,

and he used the press as his primary means. To pursue favorable publicity, he

set up an in-house press bureau. He even used a new mailing label machine to

send reports and press releases to thousands of selected individuals, groups and

newspapers.

The broad support he generated coupled with President Theodore

Roosevelt's vigorous backing gave Pinchot one of his greatest successes. In

1905, Congress agreed to transfer all national forest reserves, soon renamed

national forests, from the Department of the Interior to his agency in

Agriculture. This transfer allowed him to practice forestry on millions of

federal acres and put an end to decades of forest devastation.

During his

tenure, Pinchot increased the number of national forests from 32 to 149 and

their acreage to 193 million. Today these public lands continue to serve

multiple purposes, including watershed protection, habitat and wilderness

preservation, outdoor recreation, and timber production.

Birth of Conservation

Because of his work in forestry, Gifford Pinchot was able to bring the principle

and policy of conservation into the world.

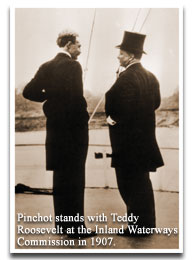

In the early 1900s, more than 20

federal agencies dealt with natural resources. Though their responsibilities

often overlapped, each agency pursued its own objectives, and little cooperation

occurred among them. Because President Teddy Roosevelt routinely conducted much

of his business with these agencies through Pinchot, who was his friend and

advisor, the chief forester became familiar with mining, agriculture,

irrigation, stream flow, soil erosion, fish, game and other resource matters

like no one else in Washington.

On a February day in 1907, Pinchot went for a

solitary ride on horseback to get away from work, but he found himself thinking

about the spectrum of natural resources-water, soil, wildlife, plants, trees and

minerals-on which our lives depend. Considering the interlocking relations among

them and that all were parts of a whole, it dawned on him that what bound all

resources together was the problem of use.

As a forester, he knew that wise use was the answer to devastation. In a leap of

imagination, he saw that an extrapolation of the idea to all resources was the key

to the future. He later remarked that "unless we practice conservation, those

who come after us will have to pay the price of misery, degradation and failure

for the progress and prosperity of our day."

Pinchot derived the name for his idea from

"conservancy," the term for a large tract of forest land managed by a

"conservator" in British India. Conservation-the management, restoration,

protection and preservation of natural resources-was his prescription for

finding a balance between human activity and the workings of nature.

Pinchot derived the name for his idea from

"conservancy," the term for a large tract of forest land managed by a

"conservator" in British India. Conservation-the management, restoration,

protection and preservation of natural resources-was his prescription for

finding a balance between human activity and the workings of nature.

When Pinchot brought his "big picture" idea to the president, Roosevelt immediately

grasped its importance. Then and there, he made it the policy of his

administration, and conservation soon became a household word.

Enduring Legacy

Though most Americans today know little about Gifford Pinchot and his launching

of the conservation movement, his legacy endures. Most of our national forests

exist largely because of his persistence. Institutions he founded 100 years ago continue to pursue their missions. Moreover, there are the countless

conservationists who have been inspired by his character, spirit, vision and

leadership.

Fred Besley was among them. Besley worked for Pinchot as a student

assistant, graduated from the Yale School of Forestry, was appointed Maryland's

first state forester in 1906, and went on to establish our state's system of

forests and parks, mirroring in part Pinchot's work for the nation. Steve Koehn,

who directs DNR's Forest Service and so holds Besley's job today, is himself a

disciple of Pinchot.

Of

course, the overarching element of his legacy is conservation itself, the core

idea guiding natural resource agencies throughout the country. In Maryland, DNR

is working diligently to replenish bay grasses, restore the oyster population,

reduce nutrient runoff, and protect the Chesapeake Bay watershed. There may be

no finer way of honoring our first conservationist than putting his idea into

practice.

Fred W.

Besley

(1872-1960)

Maryland Pioneer in Forest Conservation

In

1906, John and Robert Garrett, heirs of the B&O Railroad fortune, donated

2000 acres to Maryland on condition that the state set up a forestry

department to manage the bequest, now known as Garrett State Forest.

Maryland responded by establishing the Board of Forestry and by hiring Fred

W. Besley, our first state forester.

In

1906, John and Robert Garrett, heirs of the B&O Railroad fortune, donated

2000 acres to Maryland on condition that the state set up a forestry

department to manage the bequest, now known as Garrett State Forest.

Maryland responded by establishing the Board of Forestry and by hiring Fred

W. Besley, our first state forester.

Besley had graduated from

Maryland Agriculture College at the University of Maryland. After first

meeting Gifford Pinchot, chief of the U.S. Division of Forestry, he wrote, "Pinchot

was so boiling over with enthusiasm about forestry that then and there I

adopted forestry as my career."

1900 - Hired by

Pinchot as a student assistant for fieldwork at $25 a month; assigned to

survey timber in New York, Michigan, and Kentucky

1903 - Graduated cum

laude with a master's degree from the Yale School of Forestry

1906 - Appointed the

first state forester of Maryland; served 36 years

1913 - Began the

Timber Marking Plan, a program providing private landowners with assistance

in designating trees suitable for harvest; this practice became standard

throughout the country

1916 - Published

"The Forests of Maryland," the first comprehensive survey of forest

resources conducted by any state; later wrote, "I trampled every cow path in

Maryland making it"

1924 - Initiated the

first statewide Big Tree Contest; worked with the American Forestry

Association to launch the national Big Tree Contest in 1940 (Maryland's Wye

Oak held title as the nation's largest white oak until its toppling in 2002)

Note: This article originally appeared in the Fall 2004

issue of The Maryland Natural Resource magazine.