Recognizing the Contributions of the Civilian Conservation Corps (C.C.C.) to Maryland's State Forests & Parks

Recognizing the Contributions of the Civilian Conservation Corps (C.C.C.) to Maryland's State Forests & Parks

Part I: A

National Perspective:

Conservation Under Roosevelt

CCC enrollees throughout the country were

credited with renewing the nation's decimated forests by planting an

estimated three billion trees from 1933 to 1942.

The 1932 Presidential election was more a cry for help from a desperate

people near panic as it was an election in a "landslide" vote. The nation turned

to Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the Democratic party in search of an end to the

rampant unemployment and economic chaos that gripped the country. They weren't

disappointed. Accepting the Presidential nomination on July 1, 1932, New York

Governor Roosevelt planned a fight against soil erosion and declining timber

resources, utilizing the unemployed of large urban areas.

Professional foresters and interested layman raised these

aims. In what would later be called "The Hundred Days," President Roosevelt

revitalized the faith of the nation with several measures, one of which was the

Emergency Conservation Work (ECW) Act, more commonly known as the Civilian

Conservation Corps. With this action, he brought together two wasted resources,

the young men and the land, in an effort to save both.

The President wasted no time: He called the 73rd Congress

into Emergency Session on March 9, 1933, to hear and authorize his program. He

proposed to recruit thousands of unemployed young men, enroll them in a

peacetime army, and send them into battle against destruction and erosion of our

natural resources. Before it was over, over three million young men engaged in a

massive salvage operation, the most popular experiment of the New Deal. Senate

Bill 5.598, introduced in March 27, 1933, passed both houses of Congress and was

on the President's desk to be signed on March 31, 1933.

The President wasted no time: He called the 73rd Congress

into Emergency Session on March 9, 1933, to hear and authorize his program. He

proposed to recruit thousands of unemployed young men, enroll them in a

peacetime army, and send them into battle against destruction and erosion of our

natural resources. Before it was over, over three million young men engaged in a

massive salvage operation, the most popular experiment of the New Deal. Senate

Bill 5.598, introduced in March 27, 1933, passed both houses of Congress and was

on the President's desk to be signed on March 31, 1933.

The speed with which the plan moved through proposal,

authorization, implementation and operation was a miracle of cooperation among

all branches and agencies of the federal government. It was a mobilization of

men, material and transportation on a scale never before known in time of peace.

From FDR's inauguration on March 4, 1933, to the induction of the first enrollee

on April 7, only 37 days had elapsed.

Logistics was an immediate problem. The bulk of young

unemployed youth was concentrated in the East, while most of the work projects

were in the western parts of the country. The Army was the only agency with the

slightest capability of merging the two and was in the program from the

beginning. Although not totally unprepared, the Army nevertheless devised new

plans and methods to meet the challenge. Mobilizing the nation's transportation

system, it moved thousands of enrollees from induction centers to working camps.

It used its own regular and reserve officers, together with regulars of the

Coast Guard, Marine Corps and /Navy to temporarily command camps and companies.

The Army was not the only organization to evoke

extraordinary efforts to meet the demands of this emergency. Agriculture and

Interior were responsible for planning and organizing work to be performed in

every state of the union. The Department of Labor, through its state and local

relief offices, was responsible for the selection and enrollment of applicants.

All four agencies performed their minor miracles in coordination with a National

Director of ECW, Robert Fechner, a union vice-president, personally picked by

FDR and appointed in accordance with Executive Order 6202, dated April 5, 1933.

The Army was not the only organization to evoke

extraordinary efforts to meet the demands of this emergency. Agriculture and

Interior were responsible for planning and organizing work to be performed in

every state of the union. The Department of Labor, through its state and local

relief offices, was responsible for the selection and enrollment of applicants.

All four agencies performed their minor miracles in coordination with a National

Director of ECW, Robert Fechner, a union vice-president, personally picked by

FDR and appointed in accordance with Executive Order 6202, dated April 5, 1933.

Never before had there been an agency like the CCC.

The administration of the CCC was unprecedented. The same Executive Order

that authorized the program and appointed Robert Fechner as Director of

the Emergency Conservation Work Act (ECW), also established an Advisory

Council composed of representatives of the Secretaries of War, Labor, and

Agriculture and Interior. This Council served for the duration. It had no book

of rules. There were none. It was an experiment in top-level management designed

to prevent red tape from strangling the newborn agency.

The program had great public support. Young men flocked to

enroll. A poll of Republicans supported it by 67 percent, and another 95 percent

of Californians were for it. Even Colonel McCormick, publisher of the Chicago

Tribune and an implacable hater of Roosevelt, gave the CCC his support. The

Soviet Union praised the program…perhaps it saw a touch of socialism. A Chicago

judge thought the CCC was largely responsible for a 55 percent reduction in

crime by the young men of that day.

By April 1934, the young and inexperienced $30-a-month

labor battalion had met and exceeded all expectations and the impact of

mandatory monthly $25.00 allotment checks to families was felt in the economy of

the cities and towns all across the nation. In communities close to the camps,

local purchases averaging about $5,000 monthly staved off failure of many small

businesses. The man on the radio could, for a change, say, "There's good news

tonight."

News from the camps was welcome and good. The enrollees

were working hard, eating hearty and gaining weight, while they improved

millions of acres of federal and state lands, and parks. New roads were built,

telephone lines strung and the first of millions of trees that would be planted

had gone into the soil. Glowing reports of the accomplishments of the Corps were

printed in major newspapers, even in some that bitterly opposed other phases of

the New Deal. President Roosevelt, well pleased with his "baby," announced his

intention to extend the Corps for at least another year.

News from the camps was welcome and good. The enrollees

were working hard, eating hearty and gaining weight, while they improved

millions of acres of federal and state lands, and parks. New roads were built,

telephone lines strung and the first of millions of trees that would be planted

had gone into the soil. Glowing reports of the accomplishments of the Corps were

printed in major newspapers, even in some that bitterly opposed other phases of

the New Deal. President Roosevelt, well pleased with his "baby," announced his

intention to extend the Corps for at least another year.

In 1935, the Civilian Conservation Corps

began the best

years of its life.

Behind it, for the most part, were early days of drafty tents, ill-fitting

uniforms and haphazard work operations. Individual congressmen and senators were

quick to realize the importance of the camps to their constituencies and

political futures. Soon, letters, telegrams and messages flooded the Director's

office most of them demanding the building of new camps in their states.

Eventually there would be camps in all states and in Hawaii, Alaska, Puerto Rico

and the Virgin Islands. By the end of 1935, there were over 2,650 camps in

operation in all states. California had more than 150. Delaware had three. CCC

enrollees were performing more than 100 kinds of work.

The years 1935-36 witnessed not only a peak in the size and

popularity of the Corps but revealed the first major attempt to change a system

which had proved to be workable and successful since early in 1933. However,

before this challenge developed, Congress authorized funded and extended the

existence of the CCC until March 1935, with a new ceiling of 600,000 enrollees.

This action left little doubt that the "grass roots" and their representatives

were more than satisfied with the work of the Civilian Conservation Corps.

At first, it appeared there would be no problems in

reaching the 600,000-man ceiling. However, a new name had appeared among

Roosevelt's advisors. Harry Hopkins established new and uncoordinated ground

rules for the selection of enrollees. His procedure, based on relief rolls,

effectively ruined the quota systems in use by all the states. Fechner protested

violently, and the hassle that developed slowed down the recruiting efforts and

generated so much confusion that by September 1935, there were only about

500,000 men located in 2,600 camps. Never again, during the remainder of the

life of the Corps, were there as many men in as many camps.

At first, it appeared there would be no problems in

reaching the 600,000-man ceiling. However, a new name had appeared among

Roosevelt's advisors. Harry Hopkins established new and uncoordinated ground

rules for the selection of enrollees. His procedure, based on relief rolls,

effectively ruined the quota systems in use by all the states. Fechner protested

violently, and the hassle that developed slowed down the recruiting efforts and

generated so much confusion that by September 1935, there were only about

500,000 men located in 2,600 camps. Never again, during the remainder of the

life of the Corps, were there as many men in as many camps.

Despite a few problems, the year 1936 was a success for the

CCC. The projects completed had reached high levels, all faithfully recorded and

reported to FDR in Fechner's yearly report. It was a proud record, added to each

year, so that in 1942, there was hardly a state that couldn't boast of permanent

projects left as markers in the passage of "Roosevelt's Tree Army."

Some of the specific accomplishments of the Corps during

its existence included 3,470 fire towers erected, 97,000 miles of fire roads

built, 4,235,000 man-days devoted to fighting fires, and more than three billion

trees planted. Five hundred camps were under the control of the Soil

Conservation Service, performing erosion control. Erosion was ultimately

arrested on more than twenty million acres. The CCC made outstanding

contributions in the development of recreational facilities in national, state,

county and metropolitan parks.

The Civilian Conservation Corps approached maturity in

1937.

Hundreds of enrollees had passed through the system and returned home to

boast of their experiences, while hundreds more demonstrated their satisfaction

by extending their enlistments. Life in the camps had settled down to almost a

routine, with work the order of the day, every day, except Sunday. But, after

the evening meal the camps came to life as well over a hundred men relaxed and

had fun. One building in every camp was a combined dayroom, recreation center

and canteen, or PX. In this building, amid the din of Ping-Pong, poker,

innumerable bottles of "coke", and occasional beers, were fostered friendships

that exist to this day. This, then, was the Civilian Conservation Corps that FDR

tried to make permanent in April, 1937.

There were many reasons why Congress refused to establish

the Corps as a permanent agency. At the time, most of them were probably valid.

But never were disenchantment, or failure to recognize the success of the

organization, a topic of debate. To the contrary, in a vote of confidence,

Congress extended its life as an independent, funded agency for an additional

two years. Conceivably Congress still regarded the CCC as a temporary relief

organization with an uncertain future, rather than as a bold, progressive

solution to the continuing problem of dissipation of our national resources.

Whatever the reason, this stunning contradiction was a personal defeat for the

President and a punitive restatement of congressional independence.

The Corps itself continued to be popular. Congress, with an

eye to the folks back home, added $50 million to the CCC's 1940-41 appropriation

and the Corps remained at its current strength of about 300,000 enrollees.

Congress would never again be as generous. Other major problems were developing

within Congress, most related to the defense of the country, and, inevitably,

with each crisis, the priority and prestige of the CCC suffered.

By late summer, 1941, it was obvious the Corps was in

serious trouble

Lack of applicants, desertion, and the number of enrollees leaving for jobs had

reduced the Corps to fewer than 200,000 men in about 900 camps. There were also

disturbing signs that public opinion had been slowly changing. Major newspapers

that had long defended and supported the Corps were now questioning the

necessity of retaining the CCC when unemployment had practically disappeared.

Most agreed there was still work to be done, but they insisted defense came

first.

Pearl Harbor had shaken the country to its very core, and

it soon became obvious that in a nation dedicated to war any federal project not

directly associated with the war effort was in trouble. The joint committee of

Congress authorized by the 1941-42 appropriations bill was in session

investigating all federal agencies to determine which ones, if any, were

essential to the war effort. The CCC came under review late in 1941. The major

report recommended the Civilian Conservation Corps be abolished by July 1, 1942.

The CCC lived on for a few more months but the end was inevitable.

Technically the Corps was never abolished.

It was far simpler for Congress just to refuse it any additional money. This the

House did in June, 1942, by a narrow vote of 158 to 151. The Senate voted twice

and then Vice-President Henry Wallace, to break the tie, voted to fund the CCC.

It was a valiant effort, but it didn't work. The Senate-House conference

committee compromise finished it by concurring in the House action in return for

$8 million to liquidate the agency. The full Senate confirmed the action by

voice vote and the Civilian Conservation Corps moved into the pages of history.

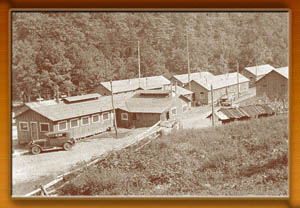

Photographs (top to botttom):

-

Franklin Delano Roosevelt with CCC boys

-

Robert Fechner, 4th from left, and party at Indian Head,

Maryland, 1938

-

CCC Camp in Western Maryland

-

CCC Work Crew

Acknowledgements:

The National Perspective article

above was created from excerpts from the National Association of Civilian

Conservation Corps Alumni website.