The Civilian Conservation Corps

The Civilian Conservation Corps

Roosevelt's Tree Army in Maryland

Part III: 100th Anniversary CCC Plaque Dedication and Personal

Perspectives

On

Sept. 17, 2006, nine veterans of Roosevelt's Civilian Conservation Corps joined DNR Secretary Ron Franks for the commemoration of their efforts with a new plaque at Gambrill State Park.

Remarks by DNR Secretary Ronald C.

Franks

The Civilian Conservation Corps -- truly one of the most spectacularly

successful public works project in American history -- was born of the

despair of the Great Depression in the 1930s. It was the era of soup

kitchens, Hoover Villages, and “The Grapes of Wrath.”

Part

of President F.D. Roosevelt’s famous “Hundred Days Legislation” to get the

nation back on its feet was the Emergency Work Act, one aspect of which

established the CCC. The CCC recruited millions of young, unemployed men

across the nation to perform conservation work in forests, parks, on

waterways and even on private property, to reclaim the nation’s natural

resource base. Government could work amazingly fast in those days: FDR

signed the Emergency Work Act on March 27, 1933, and the first camp opened

in Virginia only 21 days later! By the first of July, 270,000 enrollees

were serving in 1,300 camps across the nation.

Part

of President F.D. Roosevelt’s famous “Hundred Days Legislation” to get the

nation back on its feet was the Emergency Work Act, one aspect of which

established the CCC. The CCC recruited millions of young, unemployed men

across the nation to perform conservation work in forests, parks, on

waterways and even on private property, to reclaim the nation’s natural

resource base. Government could work amazingly fast in those days: FDR

signed the Emergency Work Act on March 27, 1933, and the first camp opened

in Virginia only 21 days later! By the first of July, 270,000 enrollees

were serving in 1,300 camps across the nation.

The CCC boys were organized into 200-man companies, and assigned work

camps across the nation. The U.S. Army provided discipline, camp officers,

quarters, food, and medical care. Federal, state and local authorities

designated work projects, trained the boys to do the work, and provided

oversight of the work. The boys themselves received discipline, hearty

food, clothing, shelter, medical care, educational opportunities, and,

most importantly of all, a sense of hope and purpose. Their monthly pay

was $30 -- $25 of which was sent home to their families. These pay

disbursements alone had a significant impact on the national economy.

By the time World War II superseded the CCC, nearly 3 million young men

had served, and they had enhanced millions of acres of natural resources

and historic sites across the nation.

Maryland benefited hugely from the CCC. Over 30,000 CCC boys served in

our state, at over 60 camps. Together they:

- built 274 bridges;

- constructed 3,500 erosion check dams;

- planted four and a half million trees;

- improved over 60,000 acres of forests stands;

- and reduced fire hazards on over 23,000 acres.

The CCC boys also built the first major state park facilities in Maryland:

- Herrington Manor (cabins and lake)

- Swallow Falls (pavilions, trails, camp sites)

- Big Run

- New Germany (cabins, lake, pavilions)

- Gambrill (all you see here, including this overlook where we are

standing, was built by the CCC)

- Elk Neck (cabins)

- Fort Frederick (the fort’s walls were restored and support

facilities built)

- Washington Monument (the monument was reconstructed, picnic

pavilions and support facilities were built)

- Patapsco Valley (trails and pavilions)

- Cedarville

- Pocomoke (a public fishing pier)

If ever a debt of gratitude was owed by a present generation to a past

one, our nation and state owe a huge one to the work of the Civilian

Conservation Corps.

- Address delivered by C. Ronald Franks, Secretary

Maryland Department of Natural Resources

Gambrill State Park, Sept. 17, 2006

Park Service Veterans Gather for Reunion

By Geoffrey D. Brown

News-Post Staff

FREDERICK — Clarence

Simmons, 88, stood a few yards from Gambrill State Park's Frederick

Overlook and admired the stone he hauled almost 60 years ago.

FREDERICK — Clarence

Simmons, 88, stood a few yards from Gambrill State Park's Frederick

Overlook and admired the stone he hauled almost 60 years ago.

Maryland's parks are

what they are in large part due to the work of almost 40,000 young men who

swept into the state from 1933 to 1942 and labored in dozens of camps,

restoring forests, building shelters and cabins and fire towers, blazing

trails and fighting fires.

On Sunday nine veterans

of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's storied Civilian Conservation Corps

returned for the commemoration of their efforts with a new plaque at

Gambrill State Park. Fifteen had been invited. One had died since the

invitations were sent.

The ceremony was part of

the Maryland Park Service's 100th anniversary celebration. Joining the

ceremony also were family members of Maryland's first State Forester, Fred

W. Besley, who was among a handful of conservationist pioneers nationwide.

Mr. Besley had a staff

of 25 at most before the CCC boys arrived. The "tree army" of unemployed

boys and young men earned $30 a month to start — $25 of it sent home to

family — in Roosevelt's jobs program, which aimed to restore the land and

put unemployed men to work.

"It was the greatest

shot in the arm the young forestry department could have had," said Offutt

Johnson, a retired state naturalist who worked closely with Frederick

County officials to establish and improve parks in the county.

"It was the greatest

shot in the arm the young forestry department could have had," said Offutt

Johnson, a retired state naturalist who worked closely with Frederick

County officials to establish and improve parks in the county.

Mr. Simmons, who now

lives in Hagerstown, worked in several state parks, and drove a truck

carrying rock to construction sites, and ferrying workers to and from the

camp on what is now Old Camp Road.

Joe Bianchini, 85, of Mount Rainier, visited with his wife Anita, and they both recalled their own service to the country. Mr. Bianchini, who grew up in the Bronx, New York City, took the train with 500 CCC boys and wound up in Idaho, where

he repaired roads. Ms. Bianchini was a riveter at an airplane factory

during World War II.

John Patrick Curley, 89, of Spring Ridge spent six years in eight camps and learned what was to be his lifelong trade as an operating engineer, running heavy construction equipment.

Joseph Decenzo, 88, of

Clinton, Md., was a camp clerk, became a leader at the Sligo, Pa. camp at a whopping $45 a month, and was a star on camp baseball, softball and basketball teams. Keith Paugh, 81, of Middle River, Md., was a truck driver at the New Germany, Md. camp, and made $36 a month as an assistant leader.

Joseph Decenzo, 88, of

Clinton, Md., was a camp clerk, became a leader at the Sligo, Pa. camp at a whopping $45 a month, and was a star on camp baseball, softball and basketball teams. Keith Paugh, 81, of Middle River, Md., was a truck driver at the New Germany, Md. camp, and made $36 a month as an assistant leader.

"I didn't spend all the

money, either, did you?" Mr. Paugh asked Mr. Decenzo.

"No, I didn't either,"

Mr. Decenzo said.

A movie cost 15 cents, a

pack of cigarettes a nickel.

George Smith, 81, of

Bowie, showed off a small, battered tin frame with a black-and-white photo

of himself in his CCC uniform, aged 18. The photo and frame cost a dime.

Mr. Smith joined the CCC while still in high school in June of 1941. In

September he went back to school. That December, the Japanese bombed Pearl

Harbor, and in January 1942 Mr. Smith joined the Navy.

In Maryland, the CCC

built 274 bridges, installed 3,500 check dams to preserve trails, planted

4.5 million trees, and improved over 60,000 acres of park land.

"All you see here,

including this overlook where we're standing, was built by the CCC boys,"

C. Ronald Franks, secretary of the Maryland Department of Natural

Resources, told the gathering.

"Our nation and our

state owe a debt of gratitude to the CCC."

Note: The above article, "Park service veterans gather for

reunion," by Geoffrey D. Brown, News-Post Staff

is reprinted here with permission of the Frederick News-Post and Randall

Family, LLC as published on September 18, 2006. Maryland DNR and the

Centennial Committee would like to thank Mr. Brown for his thorough

coverage of this event.

New Germany Remembers the CCC

By Bill Martin

One bright, sunny

morning in June 1933 a convoy of covered stake-body and dump trucks

appeared at New Germany. They carried tents, field kitchen, water

purification equipment, clothing, tools and a cadre of regular army

enlisted men from Fort Meade. New Germany was designated Civilian

Conservation Corps (CCC) Company 326, S-52.

One bright, sunny

morning in June 1933 a convoy of covered stake-body and dump trucks

appeared at New Germany. They carried tents, field kitchen, water

purification equipment, clothing, tools and a cadre of regular army

enlisted men from Fort Meade. New Germany was designated Civilian

Conservation Corps (CCC) Company 326, S-52.

The trucks would be used

to transport the company of CCC enlistees to the temporary site. All

equipment and supplies were off-loaded into the field and the covered

trucks were dispatched to Meyersdale, PA. The men had traveled from

Baltimore via the B&O Railroad. The convoy returned in late afternoon with

a bedraggled crew. Some of the men had never been out of the city before

and were unprepared for camp life.

The minimum age for

enlistment was 18, but in the camp at New Germany there were frequently

lads of 14 and 15. Enlistment was for six months but could be extended.

The first problem was

providing shelter for 150 men. Piles of canvas laying on the ground, their

new homes, had to be assembled before they could sleep. A field kitchen

was set up and supper served. Bedding was issued. Eight to a tent, the men

were bedded down for the night. In addition to the usual complement of 120

men, there was a first sergeant, supply sergeant, mess sergeant and

company clerk. Officers included a company commander, adjutant and doctor.

These were reserve officers called to active duty by Congress.

The tent city included

squad tents, officers' tents and supply tent. The orderly room and

dispensary tents were then set up for operation. The field kitchen was in

the center. All meals were served from that facility. Slit trenches were

used initially and later outside toilets were built.

The tent city included

squad tents, officers' tents and supply tent. The orderly room and

dispensary tents were then set up for operation. The field kitchen was in

the center. All meals were served from that facility. Slit trenches were

used initially and later outside toilets were built.

All water was trucked

into the camp. Drinking water was available in Lister bags throughout the

camp. The only bath facility was the lake. After several days

orientation, the boys were issued: clothing and equipment. This included

a mess kit - two flat pans hinged together, a knife, fork and spoon, solid

aluminum cup and a canteen.

Each boy was issued blue

dungaree trousers, coats and a round blue hat as a work uniform. Olive

drab (OD) shirts and pants completed the dress uniform. An overseas hat

and overcoat were issued later in the year. Other wardrobe items included

a raincoat, galoshes, ties, gloves, shoes, socks, underwear towels and

long johns.

At the onset everything

was one size (too big). It took some time to fit each individual. But

everyone had something to wear.

The first big project

was to build platforms for the tents. The tents were erected on the

platforms. When stretched tightly and tied down, it was very cozy

inside. A space heater was installed in each tent. The first winter at

New Germany was spent in tents.

The field kitchen served

three meals each day. Kerosene stoves were used for cooking. A large

gasoline generator in the woods east of the tent city provided

electricity. It supplied power for the Refrigerators, officers' tents,

dispensary and orderly room. Enlistees used candles and kerosene lanterns

in the squad tents.

At mealtime, the entire

company would assemble in a line at the field kitchen. Meals were served

cafeteria style. In inclement weather, mess kits were carried back to the

tents. At other times, the CCC boys ate under the shade of the nearest

tree. The quality and quantity of the food served from the field kitchen

was outstanding. Most boys never ate any better at home. Most of the

food was locally produced.

At mealtime, the entire

company would assemble in a line at the field kitchen. Meals were served

cafeteria style. In inclement weather, mess kits were carried back to the

tents. At other times, the CCC boys ate under the shade of the nearest

tree. The quality and quantity of the food served from the field kitchen

was outstanding. Most boys never ate any better at home. Most of the

food was locally produced.

After eating, the boys

sterilized their kits. They scrubbed their kits in a can of boiling soapy

water and then double-rinsed in a can of clear boiling water.

Periodically they scoured kits with sand to shine them. Woe unto anyone

found with a dirty mess kit.

One of the first

permanent buildings was the mess hall. Construction began in the fall of

1933. The building was 200 by 30 feet with the kitchen about halfway on

the east side. At the north end the supply room held staples and canned

goods and a refrigerated compartment. The south end was the officers’

mess.

The kitchen was modern. Hotel ranges fired with coal were used for cooking and baking. A serving

line formed on the east side of the mess. Picnic tables were used in the

hall. A generator supplied lights. Heat came from three large space

heaters.

After several months of

operation, the camp commander enlisted local men as trainers and

supervisors. This category of enlistees, known as local experienced men (LEMs),

was permitted to live at home. They earned several dollars more per

month, wore uniforms and were subject to the same rules and regulations as

the others.

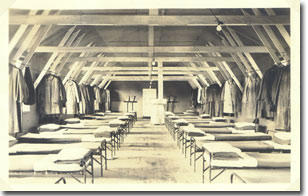

Next came the

construction of permanent quarters. Local carpenters supervised

construction of six 80 by 30 feet barracks on poles east of the recreation

hall. There were three barracks on each side, with a company area and

flag pole in the center.

These barracks were not

occupied by the company members until late spring 1934. The winter spent

in tents acquainted everyone with the hardships of winter.

The recreation hall was the

center of camp life. The rec hall is little changed from when it was

built. There were several pool tables and tennis table games. Books and

writing materials were available. Gambling was prohibited, but there was

usually some sort of card game being played. The canteen was located in

the alcove that now houses the snack bar. It was open daily and catered to

personal needs. North of the recreation hall was a combination bath

house/toilet. This heated facility was welcome after almost a year

without showers or toilet facilities.

The recreation hall was the

center of camp life. The rec hall is little changed from when it was

built. There were several pool tables and tennis table games. Books and

writing materials were available. Gambling was prohibited, but there was

usually some sort of card game being played. The canteen was located in

the alcove that now houses the snack bar. It was open daily and catered to

personal needs. North of the recreation hall was a combination bath

house/toilet. This heated facility was welcome after almost a year

without showers or toilet facilities.

The barracks were

not occupied by the company members until late spring 1934. The winter

spent in tents acquainted everyone with the hardships of winter. By early

summer of 1934, the majority of the permanent buildings had been completed

and were in use.

With most of the

buildings completed, the CCC boys formed crews to build roads. These

included from the top of Savage

Mountain to the High Rock Tower. In the winter, most of the roads were

shoveled by the CCC boys. Snow plows did not venture onto the back roads.

The timber used to build

the cabins and picnic shelters was cut and sawed by Sam Otto on his

sawmill. Fire control was another duty during fire season.

In the winter, most of

the roads were shoveled by the CCC boys. Snow plows did not venture onto

the back roads. Camp personnel eventually built a wooden snow plow pulled

by a small tractor. The summer of 1934 saw the rebuilding of the

breast of the lake. It was just a jumble of rocks stumps and logs. The

lake was completely drained and the existing breast completely removed.

The present earthen breast works were built along the spillway.

In the winter, most of

the roads were shoveled by the CCC boys. Snow plows did not venture onto

the back roads. Camp personnel eventually built a wooden snow plow pulled

by a small tractor. The summer of 1934 saw the rebuilding of the

breast of the lake. It was just a jumble of rocks stumps and logs. The

lake was completely drained and the existing breast completely removed.

The present earthen breast works were built along the spillway.

The lake was drained

several times between 1934 and 1938 for purpose of stump and log removal. The bigger fish were taken to Sam

Otto's pond. It was not unusual to catch brown and rainbow trout from the

catch pen below the spillway that were 30 inches in length. Most other

fish were allowed to enter Poplar Lick and eventually made their way into

Savage River.

Most boys gave a day's

work for a day's pay. Foremen did not work anyone beyond his ability.

Malingerers, gold brickers and malcontents were 'fired' from their jobs

and returned to camp. They cleaned out grease traps in the kitchen or

joined the "honey bucket brigade" cleaning out the toilets. After several

days they were overjoyed to return to their job on the road or in the

woods. Periodically, a vaudeville show would perform at the camp. This

was usually well attended by both camp personnel and local citizens.

The generators were shut

down after 9 p.m. One was kept running to provide lights for fire exits

and the orderly room. "Lights out” was strictly observed. Some

individuals circumvented this policy by hiding under the covers with a

flashlight to read or write letters.

Church services were

held at the rec hall on Sunday providing there was a chaplain available.

He was known as "Holy Joe." If no chaplain was available, those who wished

to attend church were taken to local churches. Movies were shown in the

rec hall several times each week. They were free to the camp personnel.

Local citizens were charged five cents. If you didn't have the nickel,

you were welcome anyway. Saturday night was a special night. This was

Liberty Run night. The boys were loaded into the covered trucks and taken

to Frostburg or Lonaconing.

Being close to a body of

water was a great temptation to many of the boys. Some of them could not

swim so in the summer of 1934, and every summer thereafter, water safety

courses and swimming instruction were given to anyone who was interested.

In 1938, CCC Company 326

at New Germany was disbanded. All men and equipment was moved to Meadow

Mountain camp, S-68.

Note: This story

originally appeared in the Fall 1990 issue of Parkline. Billy Martin grew

up working at the newly-created New Germany State Park with his father,

the first state forester at Savage River State Forest. After World War

11, Martin worked at New Germany and Patapsco before reenlisting in the

Air Force from which he retired in 1965. He returned to the Grantsville

area and beginning in 1985 he served as a contractual employee 10 months out of

the year at New Germany. He volunteered his time during the other two

months and inherited the job of historical interpreter.

Acknowledgements:

The editor of this article gratefully acknowledges the

following persons whose contributions made it possible to present this

perspective of the CCC in Maryland. Where errors may occur, Maryland DNR

will sincerely appreciate any corrections, clarification or additional

comments from former CCC members and their families, or from historians

who may have a more accurate factual record.

-

"Park service veterans gather for reunion,"

by Geoffrey D. Brown, Frederick News-Post,

is reprinted

here with permission of the Frederick News-Post and Randall Family, LLC as

published on September 18, 2006. Maryland DNR and the Centennial

Committee would like to thank Mr. Brown for his thorough coverage of this

event.

-

"New Germany Remembers the CCC," by Billy Martin. This story

originally appeared in the Fall 1990 issue of Parkline. Billy Martin grew

up working at the newly-created New Germany Recreation Area with his father,

Matthew Ellis Martin, the first Resident Warden at Savage River State Forest. After World War

11, Martin worked at New Germany and Patapsco before reenlisting in the

Air Force from which he retired in 1965. He returned to the Grantsville

area and beginning in 1985 he served as a contractual employee 10 months out of

the year at New Germany. He volunteered his time during the other two

months and inherited the job of historical interpreter.

-

Photos of New Germany CCC S-52 provided with notations.

Offutt Johnson... spent most of his 35-year career with the Department

of Forest and Parks and the Dept. of Natural resources in Annapolis, Md.

For 26 of those years he worked for Program Open Space. His last ten

years with DNR, Mr. Johnson was involved in nature and history projects,

most notably at Patapsco Valley State Park where he directed the

renovation of an old stone iron workers' house into the Park's first

history center for visitors. He and his wife Joan moved to Oakland after

his retirement. He continues to volunteer by working on a history of

Maryland's state forests and parks.

Photographs (top to bottom):

- Nine veterans of the CCC with DNR Secretary Ron Franks

unveiling the CCC Centennial Plaque at Gambrill State Park, Sept. 17,

2006

- DNR Secretary Ron Franks, Francis Zumbrun as "Abraham

Lincoln Sines" in original

Maryland State Forester uniform, and Fred W. Besley, III, grandson of the

first Maryland State Forester at the CCC Centennial Plaque ceremony in at

Gambrill State Park, Sept. 17, 2006

- Pictured (l to r) are CCC Alumni, Joseph DeCenzo, Keith

Paugh, John Patrick Curley, George Smith, and Marvin Warnick.

- CCC Alumni and wife, walking to the Tea House, one of the

buildings erected by the CCC at Gambrill State Park in the thirties.

- Keith Paugh, CCC veteran who served at the New Germany CCC

Camp S-52, among others in Western Maryland, receiving a commemorative

Centennial certificate from DNR Secretary Ron Franks, Sept. 17, 2006

- New Germany CCC Camp S-52, Headquarters & Barracks of

326th Company, 1936

- New Germany CCC Camp S-52, typical Barracks Interior, 1935

- New Germany CCC boys (Camp S-52) observing an ax

demonstration

- Interior - CCC New Germany Rec Hall 1936

Resident Warden Matthew Ellis Martin (2nd row, far left)

and the CCC Camp Technical staff Camp S-52, 1936, Photo by H. C.

Buckingham, District Forester