Private Forest Landowners – Evolutions in Management

Private Forest Landowners – Evolutions in Management

Address by Kirk P. Rodgers, Besley & Rodgers, Inc.,

for the Maryland Forests Association Conference

November 2005

When my grandfather, Fred

Besley, began his task as State Forester almost 100 years ago, the condition of

privately owned forest lands in the state could only be described as

deplorable. They were over- harvested, frequently burned and little attention

was paid to reforestation. Besley concentrated his early efforts on forest

inventory, fire control and modest extension efforts to educate private forest

landowners. I can remember him describing at the family dinner table his early

efforts to educate landowners using lantern slide talks, with his son Lowell

Besley operating a slide projector powered by a small generator attached to the

back wheel of a car.

That extension work provided

by the state forestry department, coupled with the demonstration effect of good

forest management on the growing acreage of state owned lands, were some of the

tools that helped bring about the revolution in the management of privately

owned lands in Maryland that took place during the last century. But we must

also credit the ingenuity of landowners and their constant trial and error

efforts to find better sustained economic return from their forests. And we

must remember that private forest landowners have always owned the vast bulk of

Maryland’s forests. Today that figure is 78%.

To describe an evolutionary

process one needs some guideposts and historians like to define eras. One of my

favorite forest historians in Maryland, Francis Zumbrun, has used a series of

historical periods as a framework for some of his writings. Following the period

of the 1800’s, which he refers to as the

"Age of Exploitation" he described the following four periods in the 20th

century each of which has a distinct forest management style:

- The Custodial Period 1900-1940

- The Sustained Yield Management Period 1940-1970

- The Multiple Use Management Period 1970-1990

- The Sustainable and Forest Health Period 1990-present

I am going to use these

guideposts and blend in some of the 60-year history of trial and error

management on my family’s land on the Eastern Shore. In so doing I will be

telling you part of the fascinating story of the post retirement life of Fred

Besley, picking up where Francis Zumbrun left off in his talk this morning. In a

way a sub-title of part of this speech could be: “The Career of Fred W. Besley,

Part Two and Beyond.”

The Custodial Period 1900-1940

In the custodial period

private forest landowners, many of whom were farmers, responded very slowly to

the urgings of Fred Besley. They continued to burn their forests and to graze

cattle in them. This prolonged the period of degradation of forest lands

particularly in Western Maryland. On the Eastern Shore of Maryland farmers

grazed their cattle in marshes as well as on pasture. Marshes were burned each

year to improve their quality for grazing and these fires often spread into

adjacent woodlands. This was not all bad according to H. H. Chapman, a famous

forestry professor at Yale, who often referred to loblolly pine in this region

as a “fire climax species”. The gradual elimination of fire, in fact, favored

lower value hardwoods. But fire control efforts were top priority in the

Custodial Period.

Technical assistance provided

by the State slowly began to influence private forest landowners, but also

important was entry on the scene of a small group of well-trained foresters who

functioned as consultants to private landowners. The development of the science

of forestry, more specifically how to harvest trees in a way that assured their

future regeneration, was in fact the driving force of change in the Custodial

Period. “High grading” of private timber lands continued throughout much of the

state, but forest regeneration efforts gradually began to take hold.

Fred Besley had used the word

“devastated” to describe Maryland’s forest lands at the beginning of the 20th

century. He was probably referring particularly to the badly cutover, burned and

eroded forests of Western Maryland, where he spent so much of his time. But the

Eastern Shore had its own forms of devastation. Very much in evidence at the end

of the Custodial Period were huge areas of seedling and sapling sized forests

remaining after the harvest of the loblolly pine. These forests contained mostly

hardwood with suppressed pine saplings. Much of the hardwood in the wetter areas

on the Shore is of poor quality and it is common to find trees that are hollow

before reaching maturity. In the 1940’s and 50’s following World War II, many

people thought of these cutover lands as nearly worthless, which is why this

forest land was selling for $10.00 to $15.00 per acre and sometimes as low as

$5.00.

This is exactly the kind of

land that Fred Besley decided to buy when he retired from his position as State

Forester in 1942. In an interview in 1956 on the occasion of the Fiftieth

Anniversary of Forestry in Maryland he said the following: “I didn’t own an acre

of land while I worked for the state, but when I retired I decided I might as

well begin to practice what I’d preached for 36 years. By picking up a piece of

cutover land here and there in three counties, I have enough to keep me busy.”

He added: “There is no age restriction to the job of growing trees.” The article

went on to say that he had already worn out two jeeps and was working on a

third.

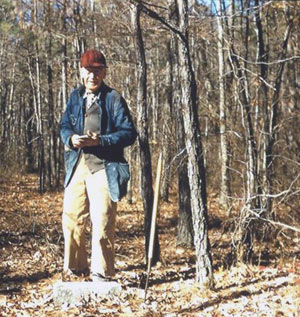

Fred Besley enjoying his favorite lunch - a

jelly sandwich accompanied by a handful of ginger snaps washed down

with water from his canteen.

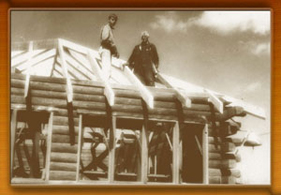

This log cabin, built by Fred W. Besley, S. Procter Rodgers and Kirk

P. Rodgers in 1949, is made from loblolly pine logs from the eastern

shore property. |

One of the few photos in existence of Fred Besley smiling. |

I can say that he had also had

worn out a teen-aged grandson who was his brush cutter and rod man for property

boundary survey. My visual memory of my grandfather while on the job was a view

of his back as he disappeared into the underbrush. He was a very fast walker! I

particularly enjoyed watching him sitting quietly eating his favorite lunch – a

jelly sandwich accompanied by a handful of ginger snaps washed down with water

from his canteen. We continued working together when I was home from college on

vacation in the Fifties and listening to him talk at the family dinner table was

an education in itself.

The

other exceptional opportunity for learning was to work at his side during the

summer of 1949 in the construction of a cabin made from loblolly pine logs from

our own land. This simple rustic building became the headquarters of our family

business on the eastern shore and a retreat for many generations of Besleys and

Rodgers. Some people have actually compared it to "the shack" of famous

environmentalist Aldo Leopold. I guess in many ways it served the same function

for the family of Fred Besley. A lot of knowledge about Maryland forestry was

imparted to family members and friends in that simple building and today it is

filled with memorabilia of the early years of forestry in this state. After

grandfather's death in 1960 my father, S. Procter Rodgers, took over management

of the family timber corporation and continued the process of trial and error to

find the best management practices for our lands.

The

other exceptional opportunity for learning was to work at his side during the

summer of 1949 in the construction of a cabin made from loblolly pine logs from

our own land. This simple rustic building became the headquarters of our family

business on the eastern shore and a retreat for many generations of Besleys and

Rodgers. Some people have actually compared it to "the shack" of famous

environmentalist Aldo Leopold. I guess in many ways it served the same function

for the family of Fred Besley. A lot of knowledge about Maryland forestry was

imparted to family members and friends in that simple building and today it is

filled with memorabilia of the early years of forestry in this state. After

grandfather's death in 1960 my father, S. Procter Rodgers, took over management

of the family timber corporation and continued the process of trial and error to

find the best management practices for our lands.

The Sustained Yield Management Period

1940-1970

|

|

Horses were still in use in 1961. They did

the job of today’s skidders, and the loader was usually a tractor using a

pine tree and boom to load the log trucks. |

Logging was still primitive in

the 1940’s and 50’s and even into the 60’s. Horses were still in use in 1961.

They did the job of today’s skidders, and the loader was usually a tractor using

a pine tree and boom to load the log trucks. But the technology evolved very

quickly, as we all know, and improved logging techniques changed the situation

dramatically.

Management efforts by private

landowners in the Sustained Yield Period were not always effective or efficient. Selective

cutting of pine, concentrating on trees with a diameter greater than 12-14

inches, was the norm in the 40’s and 50’s. I remember hearing Grandfather say

that he felt it was foolish to harvest a pine of less than 12 inches diameter.

What are you going to get he said, “a bunch of two by fours?” The contemporary

practice of selective cutting of larger pine, however, continued to favor the

hardwood on the Shore and soon came to be seen as a serious management issue.

Clear cutting began to be practiced, but the lack of a market for most of the

hardwood constituted a major obstacle. Early attempts to poison hardwoods had

uneven results. Girdling trees and using herbicides in the cuts often failed and

the cost of these labor intensive efforts was excessive.

Some

experiments we conducted on our own land were particularly instructive in this

regard. As tree harvesting machinery got more sophisticated, however, the

situation gradually improved. The big breakthrough for us was the total tree

harvester or “chipper” as it is called. This facilitated excellent site

preparation and provided a much needed market for small hardwood.

Some

experiments we conducted on our own land were particularly instructive in this

regard. As tree harvesting machinery got more sophisticated, however, the

situation gradually improved. The big breakthrough for us was the total tree

harvester or “chipper” as it is called. This facilitated excellent site

preparation and provided a much needed market for small hardwood.

To improve regeneration grandfather and my father, S. Procter Rodgers (who was

his partner), began to leave seed trees. Dad spent a lot of time

marking them as I recall. It was a novel idea in those early days and originally

we probably left too many seed trees per acre, but our experimental efforts

along with those of other private landowners contributed to the eventual

decision to pass the Maryland Seed Tree Law in 1979. Hand planting began to

replace the use of seed trees, and clear cutting was often followed by site

preparation with bulldozers, the practice we know as “sheer blade and piling”

which was used most intensively by industrial forest landowners.

Gradually clear cuts, hand

planting and aerial application of herbicides created productive pine

plantations with trees of various ages. Pine plantations on our land are often

interspersed with mixed stands of pine and hardwood, particularly in wet areas.

From the air many of our tracts look like a patchwork quilt of varying timber

types and ages. Roads have been built and carefully maintained. Timber has grown

faster and productivity of the land has increased dramatically.

The Sustained Yield Period was

good for forest production on the Shore and the increased income generated by

timber harvests proved to be a strong incentive for private forest landowners to

reforest and begin to think about the long term. During the Sustained Yield

Period, Fred Besley had the following to say in a communication to his alma

mater, the Yale Forestry School, in 1949: “I am getting some interesting

experience in multiple use of privately owned forest land. Loblolly pine lands

purchased a few years ago purely for their timber growing value are now

producing income from oil leases on a prospect basis sufficient to pay the

taxes, and the limited marsh areas are leased for the trapping of muskrats.

Other possibilities of grazing leases, holly production, fishing and hunting

privileges are being explored. In the meantime the pine is growing at close to

10% per annum. I am having to revise the argument I used before appropriation

committees to get money for the purchase of state forests, that it was only in

public ownership that these multiple use values could be fully developed.” In

this insightful statement he recognized both the evolution of management

practices on private lands in the state and the very positive role of private

landowners in these changes. He had predicted what was to come in the Multiple

Use Management Period.

Evolution of a Family of Private Forest Landowners

Evolution of a Family of Private Forest Landowners

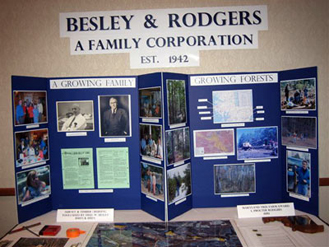

But wait, we are getting ahead of our Besley and Rodgers story. Families grow and evolve just

like forests. Grandfather and Dad recognized this early on, so in 1946 they

converted their two man partnership into a corporation. In 1974 it was

established as a close corporation under Maryland law and a stockholders

agreement was signed that assures continuity of family ownership. Stock in the

corporation is passed from one generation to another and has now spanned five

generations.

A family picture

taken in 1959 shows Fred Besley and his twin sister, Florence, seated (on the

left) next to three generations of Besleys and Rodgers. Fred Besley passed away

a little over a year after this photo was taken. He was in his late eighties,

but was still active in managing the family business. When his eyesight failed

his twin sister became his “eyes in the forest”. She accompanied him on his

tours of our forest land and on one occasion, when he wanted to know how the

young pine reproduction was doing, they both got on their knees and she guided

his hands so he could feel the young seedlings. He smiled.

I

should mention that many of the women in our family also tend to be strong and

adventurous. This is particularly true of Helen Overington, the youngest

daughter of Fred Besley, who at age 98 is here with us today accompanied by her

children and grandchildren.

In the photo on

the left they were dressed for a jeep ride on our property and were fully

prepared for the inevitable mosquitoes. The lady in the middle is Helen

Overington. The family corporation of Besley and Rodgers has grown and

evolved over more than 60 years, spanning a large part of the hundred years of

forestry in Maryland which we celebrate today.

I

should mention that many of the women in our family also tend to be strong and

adventurous. This is particularly true of Helen Overington, the youngest

daughter of Fred Besley, who at age 98 is here with us today accompanied by her

children and grandchildren.

In the photo on

the left they were dressed for a jeep ride on our property and were fully

prepared for the inevitable mosquitoes. The lady in the middle is Helen

Overington. The family corporation of Besley and Rodgers has grown and

evolved over more than 60 years, spanning a large part of the hundred years of

forestry in Maryland which we celebrate today.

|

|

| The family corporation of Besley and

Rodgers has grown and evolved over more than 60 years, spanning a large

part of the hundred years of forestry in Maryland which we celebrate

today. |

Besley & Rodgers family members group photo at the Maryland Forests Association Conference, November 2005. |

The Multiple Use Management Period 1970-1990

|

As forest management practices

intensified and forest land became more valuable, private landowners began, on

their own initiative, to diversify their operations. Hunting, which had always

been part of the culture, came to be seen as a source of serious revenue for

private landowners. Hunt clubs were organized and hunting leases were

negotiated. Landowners who had hunted their own land for generations entered

into partnerships with hunt clubs.

As forest management practices

intensified and forest land became more valuable, private landowners began, on

their own initiative, to diversify their operations. Hunting, which had always

been part of the culture, came to be seen as a source of serious revenue for

private landowners. Hunt clubs were organized and hunting leases were

negotiated. Landowners who had hunted their own land for generations entered

into partnerships with hunt clubs.

Recreational

use of private forest lands also intensified and gradually became the dominant

use of these forests in many parts of the state as we see today. On the lands of

Besley and Rodgers, outdoor recreation has always been a focus of family

activity, with hunting, fishing, camping, shooting skeet and just walking on the

land being enjoyed by generation after generation. So it is with most private

forest landowners in the state. Recreational

use of private forest lands also intensified and gradually became the dominant

use of these forests in many parts of the state as we see today. On the lands of

Besley and Rodgers, outdoor recreation has always been a focus of family

activity, with hunting, fishing, camping, shooting skeet and just walking on the

land being enjoyed by generation after generation. So it is with most private

forest landowners in the state.

|

|

|

A tree stand erected by a hunt club that leased hunting rights |

Note the Bald Eagle nest in the top of the tree. |

Preservation

of natural resources, particularly species of wildlife, also took on great

importance in the

Multiple Use Management Period. The Endangered Species Act of 1974 mandated

changes in forest practices and the private sector responded. On the Eastern

Shore the American Bald Eagle and the Delmarva Fox Squirrel commanded particular

attention. Besley and Rodgers lands are home to both. Preservation

of natural resources, particularly species of wildlife, also took on great

importance in the

Multiple Use Management Period. The Endangered Species Act of 1974 mandated

changes in forest practices and the private sector responded. On the Eastern

Shore the American Bald Eagle and the Delmarva Fox Squirrel commanded particular

attention. Besley and Rodgers lands are home to both.

Aesthetics also became

important. In the 1980’s the family, on its own initiative, set aside “Natural

Areas” which are to be permanently preserved. Aesthetically pleasing areas were

set aside also, sometimes to honor a departed family member. These areas were

sometimes created as an expanded streamside buffer. Road side as well as

streamside buffers became the norm in many areas. Efforts to help bird

populations with bird boxes became common and were often installed by hunt clubs

just for their visual enjoyment. Our forested marshes are beautiful as well as

productive places.

It is clear that during the Multiple Use Period private landowners on their own

began to take serious action to improve wildlife habitat as a routine part of

forest management. Excellent extension efforts, such as the Coverts Program of the Maryland Cooperative Extension Service, contributed

to such progress. It is clear that during the Multiple Use Period private landowners on their own

began to take serious action to improve wildlife habitat as a routine part of

forest management. Excellent extension efforts, such as the Coverts Program of the Maryland Cooperative Extension Service, contributed

to such progress.

Multiple use also expanded to

include new income-producing ventures on private forest land, such as growing

mushrooms and ginseng, pond construction and fee fishing, production of

specialty wood products including handicrafts, and many many more. As private

forest land holdings have become smaller, such uses have taken on even greater

importance and private landowners have shown a lot of imagination in developing

new ideas.

The Sustainable and Forest Health Period

1990-Present

Challenges to the private

forest landowner have greatly intensified in the Sustainable and Forest Health

Period in which we find ourselves today. According to the excellent document:

“The Importance of Maryland’s Forest: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow” published

in 2003, private forest ownership in the state has been changing dramatically.

Reflecting fragmentation of the forest land base, which is accelerating sharply,

the number of private forest landowners in Maryland increased from 35,000 to

95,000 between 1955 and 1976 and by 1989 had reached 130,000. Most disturbing,

however, is the fact that 75% of these owners hold less than 10 acres, each

property is sold on the average of once every 12 years, and only 39% of owners

have had harvest experience with their forests.

Private forest land management

is now evolving in a lot of different directions and is often driven more and

more by real estate development pressures rather than forestry considerations.

Smaller parcels and more owners make the traditional benefits of forests more

difficult to obtain and management options are more limited. Landholdings like

those of Besley and Rodgers have become a rarity.

If Grandfather Besley were

here today he would be astonished. In the early part of the century he was

concerned with the twin threats of over-harvesting and destructive fires.

Today’s urban and suburban sprawl destroys forests in a far more decisive and

permanent manner. The actions he took to control forest fires and to improve

management practices seem simple by comparison to what today’s forest managers

and private owners must grapple with.

Addressing urban sprawl, plant

diseases, insects, invasive species and loss of biodiversity require complex

solutions and involve many actors. The private landowner is going to play a

major role in finding solutions to these problems, even if he or she is not yet

aware of it. Techniques of management of private lands will continue to evolve

and new solutions to problems will be devised through a process of trial and

error just as in the past. Maryland’s forests in the future will reflect the

collective actions of these tens of thousands of land owners.

Many respected experts believe

that the role of education will become increasingly important. We face a future

in which the management of forests will be based on engaging more owners of

small parcels, many of whom do not even think of themselves as forest

landowners, but rather as owners of land which just happens to have forest on

it.

Educational approaches that

leverage limited resources must augment and perhaps replace traditional

technical assistance provided by state government. The use of volunteers, local

workshops, and local forest landowner networks like county forestry boards must

be expanded. Partnership with lawn and tree service companies to deliver

forestry services to an increasing number of small land owners who hold forest

land simply as an amenity must be given consideration. Whatever is done must be

based on a better understanding of what private landowners want, not what we

think they need. Whatever the future brings, we must learn from the past and

count heavily on the ingenuity of our private forest landowners. They had a lot

to do with bringing us to where we are today.

Acknowledgements:

Address by Kirk P. Rodgers for the Maryland Forests Association Conference Centennial Kick-off,

November 5, 2005.

Photographs (top to bottom):

-

Photo depicting the poor quality of hardwood growing in the wet

areas on the Eastern Shore. (Note that the trees hollow before reaching maturity).

-

A sapling-sized forest.

-

Fred Besley enjoying his favorite lunch.

-

One of the few photos in existence of Fred Besley smiling.

-

Log cabin, built by Fred W. Besley, S. Procter Rodgers and Kirk

P. Rodgers in 1949, is made from loblolly pine logs from the eastern

shore property.

-

Kirk P. Rodgers with his grandfather, Fred W. Besley, atop the family cabin,

which Besley built in 1949.

-

Photo depicting horses still in use for logging (as late as 1961) on the Besley Rodgers land.

-

The logging truck.

-

The total tree harvester or “chipper" as it is called.

-

Three generations of the Besley family. Fred Besley and his twin sister, Florence, are the two seated on the

left. Besley and Rodgers family women dresses for a jeep ride.

-

Company Exhibit, November 2005. The family corporation of Besley and Rodgers has

grown and evolved over more than 60 years, spanning a large part of the hundred

years of forestry in Maryland which we celebrate today.

-

Besley & Rodgers family members group photo at the Maryland Forests Association Conference, November 2005.

-

Kirk Rodgers and his wife, Karen, hunting the family property.

-

Kirk's son, Brian, with antlered sika deer.

-

A tree stand erected by a hunt club that leased hunting rights.

-

Note the Bald Eagle nest in the top of the tree.

-

Family canoeing on the nearby Blackwater River.

-

Sun setting on the forested marshes of the family property.

|