Hunters’ Valuable Contributions to Forest Conservation, Wildlife Restoration and Public Land

Acquisition

Hunters’ Valuable Contributions to Forest Conservation, Wildlife Restoration and Public Land

Acquisition

By Francis Zumbrun

Aldo Leopold, Teddy Roosevelt and Gifford Pinchot are

names that most people

recognize as great leaders of the North American

conservation movement; however,

most people probably don’t realize they were also

hunters. It has been said that

hunters were the first conservationists. Hunters,

fishermen and outdoor

enthusiasts have a close, personal attachment to the

forests, fields and streams

that support wildlife and fish habitat.

Early in the 20th century hunters including Leopold,

Roosevelt and Pinchot

recognized that certain activities such as unregulated

hunting, large-scale land

clearing, wildfires, and soil erosion were having

dramatic impacts not only on

our wildlife, but on their habitats and on forest

health as well. Along with a

growing movement of like-minded individuals, they saw

the need for stricter laws

and regulations, for government to manage and protect

both wildlife and lands,

and for sustainable funding to carry out this mission.

The abundant natural

resources that we enjoy today and the public lands

that help ensure access to

them are a testament to their efforts.

In 1936, the O’Neal family began camping and hunting

at Green Ridge State

Forest (see story below); one year later, one of the

most important pieces of federal legislation

was passed. Known as the Pittman-Robertson or Federal

Aid in Wildlife

Restoration Act, it directs that 11 percent of the

purchase price for firearms,

ammunition and archery equipment go to the federal

government and then to state

natural resource agencies for wildlife conservation.

As a result, hunters have

contributed over two billion dollars annually to

national forest and wildlife

conservation efforts since 1937.

A Century of Conservation and Recreation: Fall Color Festival, Oakland, Md. - 2006 |

|

Sportsmen have also contributed an estimated $185

million per year to forest and

wildlife conservation through the purchase of hunting

and trapping licenses or

tags. Over the last century, it is estimated that

hunters such as the O’Neal

family have contributed over $5.5 billion toward

forest and wildlife

conservation.

Hunters continue to make significant contributions to

Maryland’s economy.

According to a 2001 national wildlife survey, the

estimated annual economic

impact of deer, squirrel, turkey and grouse hunting

statewide was about $301

million. In honor of Maryland Forestry and Parks

centennial year, we pay tribute

to hunters like the O’Neal family for their

considerable contributions to forest

and wildlife conservation in Maryland.

The O’Neal Family: Seventy Years of Camping and

Hunting at Green Ridge State Forest (1936-2006)

By Francis Zumbrun

|

|

|

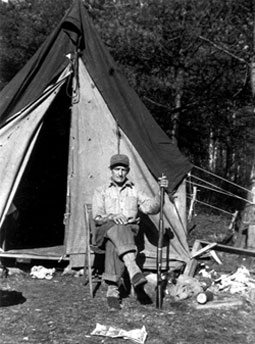

Clarence Alonzo O'Neal (circa 1936) camping and hunting at Green Ridge State Forest. The O'Neils began camping at Green Ridge five years after the State Forest was founded, and seventy years later, the family tradition continues.

|

For seventy years, five generations of O’Neal and

Murphy families have camped

and hunted at Green Ridge State Forest. I recently

stopped by the family’s

campsite on Howard Road to visit with them. On this

particular day, brothers Bob

and Jim O'Neal and their cousin Ron O'Neal, were

present.

“Your family’s been camping and hunting in Green Ridge since 1936. What keeps bringing them back?” I asked.

Bob answered simply, “We are returning to the place of our youth. Every hollow and ridge holds a memory for us.” Then he continued: “Our grandfather, Clarence

Alonzo O'Neal, started it all. He was from Mount

Savage. Rabbit hunting brought him to Green Ridge State Forest.”

I mentioned that in 1936 remnants of the famed

Mertens’ apple orchard still

existed. The orchard once provided great rabbit

habitat. Today hunters still

kick up corrugated wire tree protectors from under the

leaves on the forest

floor where apple trees once grew.

/centennial/Bacil-O'Neal.jpg

alt="O'Neil's

hunting cabin at Green Ridge State Forest, a converted

mule shed. Over the years, the O’Neals have

camped and hunted primarily at three different

locations within the 15 Mile Creek watershed at Green

Ridge. They started with

tent camping off of M.V. Smith Road near Catpoint

Road; then in the 1940s, they

converted a mule shed into a hunting cabin on the

Shircliff property, a private

tract in the forest. When their lease expired around

1969, the O'Neals returned

to tent camping, mainly on Dug Hill Road and Howard

Road.

“As kids we knew we were about to take ‘the

mountain trip’ to Green Ridge when

our grandfather announced it was time to go to camp,”

Jim said.

The O’Neals explained to me that when school let out

they spent the first two

weeks of their summer vacation at Green Ridge. “We

were dropped off at our

campsite and Grandfather O'Neal looked after us,” Jim

said. “Sometimes you’d

find us wading in the 15 Mile Creek swimming hole;

other times you’d find us

fishing.”

Grandfather O’Neal instilled respect for gun safety in

his grandchildren. “We

were told to break down a gun as soon as we walked out

of the woods and unload

immediately,” Ron explained. “Grandfather would tell

us: Don't point a gun at

anything you don't expect to kill, don't shoot

anything you don't expect to eat,

and know what you're shooting at and what's behind

it."

Jim continued, “We started hunting with supervision as

young teenagers - it was

a rite of passage. We did shoot a few groundhogs at

the age of nine, but we had

to eat them.”

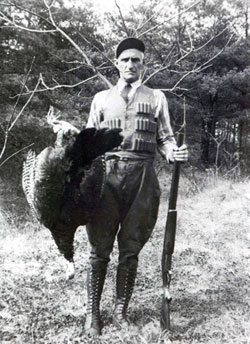

The O’Neals have never hunted deer, choosing to stick

with squirrel, grouse and

turkey. I asked them how conditions have changed at

Green Ridge over the years.

According to Ron, grouse were more plentiful in the

1950s and ‘60s. In the ‘50s,

grouse habitat was better in much of the forest

because it was in an earlier

stage of development, providing ideal ruffed grouse

habitat.

“Green Ridge State Forest was packed with hunters back

then. You coughed to let

others know you were around,” Bob remembered. “We are

proud that since 1936, no

one in our family has received a citation for a

hunting violation.”

I asked the O’Neals if they ever observed a rare

squirrel migration at Green

Ridge. My research showed that the last great squirrel

migration occurred in

1968 in the eastern United States.

Bob recalled that as teenager he observed what might

have been such a migration.

He remembered seeing large numbers of squirrels

passing at one time through the

forest, and the older men saying that the animals were

following the feed and

moving on to another area.

I shared with them a naturalist’s account recorded in

1811 of a vast migration

observed in the Ohio Valley: "A countless

multitude of squirrels, obeying some

great and universal impulse which none can know but

the Spirit that gave them

being, left their reckless and gamboling life, and the

ancient places of retreat

in the north, were seen pressing forward by tens of

thousands… to the South..."

We paused to contemplate the wonder of it all. Later

as I made to leave, the

O’Neals thanked me for visiting their campsite and

taking an interest in them.

But I thought I should be thanking them. For it is

through the significant

contributions of dedicated outdoorsmen like the

O’Neals that Maryland’s forest

health, public land acquisition, and restoration of

wildlife habitat efforts

have been possible.

Point Lookout in Green Ridge State Forest really

is one of “Maryland’s best-kept secrets.” Not to be confused with the

southern Maryland state

park of the same name, visitors to Point Lookout

have a spectacular view

of the ancient Potomac River valley. DNR

established the area around Point

Lookout as wildlands, thus protecting the view

on the Maryland side.

Visitors to Point Lookout today can enjoy the

same view that the Union

troops had 140 years ago when they used Point

lookout to observe

Confederate movements through the valley. Also

from this historic

overlook, one can survey 243 acres of land once

owned by George

Washington, first President of the United

States. Point Lookout in Green Ridge State Forest really

is one of “Maryland’s best-kept secrets.” Not to be confused with the

southern Maryland state

park of the same name, visitors to Point Lookout

have a spectacular view

of the ancient Potomac River valley. DNR

established the area around Point

Lookout as wildlands, thus protecting the view

on the Maryland side.

Visitors to Point Lookout today can enjoy the

same view that the Union

troops had 140 years ago when they used Point

lookout to observe

Confederate movements through the valley. Also

from this historic

overlook, one can survey 243 acres of land once

owned by George

Washington, first President of the United

States. |

|

|

U.S. Fish & Wildlife

Service |

|

Federal Aid in (Pittman-Robertson)

|

|

THE FEDERAL AID IN WILDLIFE RESTORATION ACT |

Where Does the

Money Come From

The Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act,

popularly know as the

Pittman-Robertson Act, was approved by Congress

on September 2, 1937, and

begin functioning July 1, 1938.

The purpose of this Act was to provide

funding for the selection,

restoration, rehabilitation and improvement of

wildlife habitat, wildlife

management research, and the distribution of

information produced by the

projects.

The Act was amended October 23, 1970, to include

funding for hunter

training programs and the development, operation

and maintenance of public

target ranges.

Funds are derived from an 11 percent Federal

excise tax on sporting

arms, ammunition, and archery equipment, and a

10 percent tax on handguns.

These funds are collected from the manufacturers

by the Department of the

Treasury and are apportioned each year to the

States and Territorial areas

(except Puerto Rico) by the Department of the

Interior on the basis of

formulas set forth in the Act. Funds for hunter

education and target

ranges are derived from one-half of the tax on

handguns and archery

equipment.

Each state's apportionment is determined by a

formula which considers

the total area of the state and the number of

licensed hunters in the

state. The program is a cost-reimbursement

program, where the state covers

the full amount of an approved project then

applies for reimbursement

through Federal Aid for up to 75 percent of the

project expenses. The

state must provide at least 25 percent of the

project costs from a

non-federal source.

- Reprinted from the

http://federalasst.fws.gov/wr/fawr.html

|

Acknowledgements:

Francis "Champ"

Zumbrun....is the forest manager at Green Ridge State Forest. He has worked as a professional

forester for DNR since 1978. He is currently

researching the life of Thomas Cresap (1694-1787),

Maryland's great pathfinder, pioneer and patriot. In

1733, Cresap cleared the Old Conestoga Road between York, PA and Union Bridge, MD. Francis is interested in hearing from anyone who has information about this

colonial road and its original alignment.

Note: Green Ridge is the second

largest of Maryland's

State Forests consisting of a 44,000-acre oak-hickory

forest. It is located in

eastern Allegany County, approximately eight miles

east of Flintstone off I-68

at Exit 64.

Read More About ...