Scientific Forestry And Urban Progressivism: The Development of the Maryland Board of Forestry, 1906 to 1921

Scientific Forestry And Urban Progressivism: The Development of the Maryland Board of Forestry, 1906 to 1921

by Robert F. Bailey

Part 4: Scientific Forestry and Urban Progressivism Converge in the Patapsco Valley

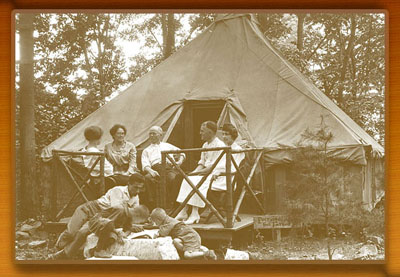

The Patapsco Forest Reserve’s recreational amenities provided middle-class suburbanites with an opportunity to blend rugged outdoor living with intellectual contemplation—or, at the very least, a chance for greater aesthetic appreciation. Campsites, in particular, were a blend of the primitive and the modern. In some cases, the influence of Baltimore’s elite progressivism was obvious—such as Victor Bloede’s philanthropic efforts and the Hutzler campsites, but in other cases the elite influence was more subtle—such as in the experiences of many other summer campers and visitors to the park. Either way, the new park provided the Forestry Board with a place to illustrate the benefits of scientific forestry to people who, for the most part, did not own large tracts of land, while simultaneously providing the white middle class with a chance to, as Besley put it, “rough it pleasantly.” Though many of Besley’s elite allies usually abstained from camping in the Patapsco—Robert Garrett, for example, typically vacationed in the Adirondacks—the State Forester himself often camped in the new park to personally spread the gospel of scientific forestry.58

In the years following the Benson bill’s passage, the Patapsco Forest Reserve rapidly took on characteristics of a public park. Land procurement proceeded quickly. Through a combination of philanthropic donations, direct purchases and negotiated easements, the Board controlled 1,665 acres by the end of 1913—a dramatic rise from the mere 43 acres it had inherited from John Glenn seven years earlier.59

As in Western Maryland, there was considerable concern over potential forests. Despite their value in fostering wildlife habitat, dead and “defective” trees were vigorously removed.60 The B&O Railroad, with the forest wardens’ assistance, cut a 100 foot-wide swath along its right-of-way, clearing out underbrush and other “inflammable material.” To “make the area thoroughly accessible,” several miles of trails were constructed and maintained. Though initially designed to fight fires, these trails quickly doubled as recreational hiking trails. In order to get a better sense of the valley’s topography “a field party was employed . . . for the purpose of preparing an accurate, large-scale . . . map to be used as a base for locating property lines and all topographical features.”61

Though the Forestry Board continued to emphasize its scientific forestry agenda, the Patapsco Reserve’s purpose now reflected the influence of Baltimore’s progressives. Rather than simply protect the forest’s timber value, the Forestry Board was now “to preserve the scenic beauty of this region.” It declared that the “lands will be maintained perpetually as a

natural forest” (my italics). This definition of “natural” was of course limited: the Forestry Board continued to practice scientific forest management in the Patapsco, but the appeal of that management now broadened. “The large number of native tree species found in this region,” the Board wrote in 1913, “together with the species that will be introduced by planting, will make a forest arboretum not only of interest to the botanist but of great educational value to the general public.” This was quite a departure from 1908 when Besley had stated that the Glenn gift would simply serve Maryland’s “timber interests.”62 Now, the Patapsco Reserve would serve the general public’s interests—especially those in the general public with the means necessary to visit the park. Though tree species at the Patapsco were in part artificially selected, just as they were in Western Maryland, trees were now evaluated for their scenic as well as economic value.

To address Baltimore City’s water-quality concerns, the Forestry Board placed protecting the Patapsco’s watershed high on its agenda. “The Patapsco area,” the Board reported, “is not only one of great natural attractiveness, being so near Baltimore that its use as a recreation grounds is certain to be more fully appreciated, but it is also important to protect the watershed of the Patapsco River, which plays such an important part in furnishing water power for several industrial enterprises.”63 These industries, which included several textile mills, a flourmill, a hydroelectric plant and a water filtration plant, directly felt the impact of sediment runoff. As the 1914/15 biannual report noted, “the steep slopes along the river that have been cultivated in years past have largely contributed to the accumulation of silt which has collected behind the dams built for storage purposes” and has forced the operators to expend “large sums of money for dredging.”64

Though all dams suffered sediment build up from increased runoff, it was Victor G. Bloede’s dams that suffered the most. A Catonsville banker with philanthropic motivations, Bloede had organized the Patapsco Electric & Manufacturing and the Baltimore County Water & Electric companies a decade earlier to supplement the region’s water and electric resources. Because his hydroelectric dam’s intakes were submerged, sediment build up was a persistent problem. The Board reported that, “this mass of sediment extending for a quarter of a mile along the river bed represents but a small part of the erosion from cultivated lands along the steep banks of the Patapsco.”65

Considering that the dam was built in 1906 illustrates the magnitude of the sediment-runoff problem. The new trees, it was hoped, would reduce the amount of silt clogging the electric plant’s turbines, plus cut the amount of energy needed to filter drinking water at Bloede’s other plant at Avalon.

With trees planted and trails blazed, efforts to open to the park up to campers moved quickly. The Board wrote, “it is proposed to offer camping sites to those who wish to take an outing here, and who probably could not afford a vacation trip to more distant places.”66 The sites were open to anyone in the state, provided that they respected the “reasonable regulations.”67 By 1916, there were 200 campsites available “for the use of the visitors who cared to use the park’s advantages.”68

“It is scenically beautiful,” wrote The Methodist. “Under the management of the Board its attractions are being protected and so far as possible enhanced”69 According to a local paper, “the State reservation is kept clean and free from forms of annoyance. The wardens, too, are alert to protect the property of campers. The reservations are not subject to prowlers, as everybody must show a permit, which in itself makes him part of the system of preserving order.”70

Like its city counterparts, the new park on the Patapsco was a means in which the middle class could enjoy the benefits of a natural environment. As a local paper put it, “Mr. Besley pictures the reserve as a real place to ‘rough it pleasantly.’”71 In 1916, Assistant Forester Dorrance reported to the

Sun the benefits available at the Patapsco Reserve. He wrote that a workingman’s “vacation weeks are the most important of his year.” Dorrance recounted that “muscles softened by disuse must be rebuilded by exercise and unaccustomed ‘stunts’ to which man has grown a stranger.” Admonishing his readers to camp at the park for extended periods, he wrote that “the vacation is not alone a let-down from the usual. To be of the greatest good, it must entail a change, and a complete one.”72

Camping in the Patapsco, therefore, offered a perfect opportunity for both physical and contemplative recreation. A group that spent the fall camping a Patapsco wrote in the Sun, “we are now located there [Patapsco Forest Reserve], and any weekend will find from 20 to25 of our faithful band of Gypsies enjoying nature to its fullest extent.” The participants exulted that they were “enjoying watching the change of foliage from week to week, taking dips in the old Patapsco river in spite of the frost, getting up at 4 A. M. to watch the daybreak, walking eight miles to church in the morning and chopping wood, preparing meals, washing dishes and taking trips through the reserve during the day.”73 The

Methodist recounted that “individuals by scores, have already proved the Patapsco much of their liking. Community camps of families brought together by residential, religious, or social ties afford good opportunity for profitable association in a way that makes finer and better friends.”74 According to the Sun, all the visitors “liked its fishing, swimming and canoeing, their campsites, and the supply of drinking water from the springs.”75 Campers were even permitted to plant vegetable gardens. “In fact,” wrote the

Methodist, “there is every disposition to encourage the deeper, broader application of “rusticating and vacation camping practice.”76

Elaine Hamilton O’Neal, an artist born in Catonsville, spent a portion of her childhood growing up in the Patapsco Reserve. During the 1920s, her parents and two brothers spent five months out of the year living in an army-style wall tent near Orange Grove. “We had what we needed,” she later recalled. Her experience at the park was a blend of rugged outdoor living complemented with the trappings of the modern middle-class lifestyle. Her family, on the one hand, was forced to dig a privy, sleep on straw mattress cots, and make several trips a day down to the local spring for fresh water; however, on the other hand, they cooked on a modern oil stove, owned a piano, and had electric power wired in from Bloede’s Dam for lighting and a radio. Groceries and supplies were acquired by walking over a mile once a week to a nearby mill town. By carving out a place to live in the wilderness, O’Neal asserted that she was able to develop self confidence and a sense of adventure, and she “learned to be creative and inventive.” At the park, she discovered how to paint and swim, and she developed an acute hearing ability and “a strong sense of smell.” O’Neal learned to identify sounds made by owls, song birds and wild turkeys, and how to avoid copperhead snakes. With few other children around, O’Neal developed a stronger relationship with her brothers. Her experiences at the park, she believes, played a critical role in her eventual status as a Fulbright Scholar and career as an artist. In this sense, O’Neal’s experience at the Patapsco exemplified the white middle-class desire to identify with the rugged experience of the working classes while attaining the intellectual and cultural standards typified by the upper classes. O’Neal’s experience at the Patapsco was simultaneously rugged and refined.77

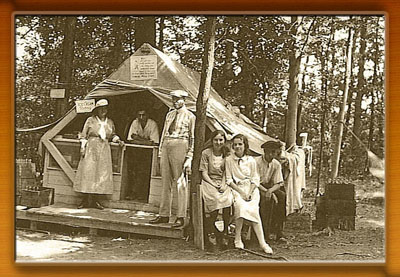

Perhaps the most explicit example of elite philanthropy playing a role in shaping middle-class values, however, were the Hutzler campsites. During the summer months, the Hutzler Department Store Company reserved dozens of sites for their male employees, primarily sales clerks, and their families. While the men commuted daily to work in Baltimore, their families were left behind to enjoy the park. To foster camaraderie and loyalty, Hutzler’s

reserved sites in close proximity to one another, operated a nearby commissary,

and had ice cream delivered once a week.

In one measures success by park visitation numbers, the Forestry Board and urban

progressive efforts to expand the Patapsco Reserve into a park were successful.

By 1925, nearly 250 camping permits were issued annually, providing camping

privileges to approximately 2,500 people a year. “In addition to campers,” the

Board wrote, “there were not less than 20,000 who visited the forest for a day’s

outing” in 1924 and 1925.78 How successful they were at molding

human behavior is, of course, more difficult to measure.

58 Personal letters written by Robert Garrett to his brother John W. reveal a preference for the Adirondack Mountains and Europe. Garrett’s personal letters can be found in Special Collections at Johns Hopkins University. The Maryland Hall of Records possesses a large number of lanternslides taken at Patapsco by Besley during the early 1920s.

59 Report for 1912 and 1913, 37.

60 Report for 1912 and 1913, 37.

61 Report for 1912 and 1913, 37.

62 Report for 1912 and 1913, 36.

63 Report for 1914 and 1915, 25.

64 Report for 1914 and 1915, 26.

65 Report for 1914 and 1915, 26.

66 Report for 1912 and 1913, 37.

67 Report for 1914 and 1915, 25.

68 Baltimore Sun, Morning, July 16, 1916.

69 Baltimore Methodist, July 15, 1920.

70 Quote was taken from unidentified newspaper clipping in F. W. Besley’s scrapbook at the Maryland Hall of Records.

71 F. W. Besley scrapbook.

72 Baltimore Sun, Morning, July 16, 1916.

73 Baltimore Sun, Sunday, October 29, 1916.

74 Baltimore Methodist, July 15, 1920.

75 Baltimore Sun, Morning, July 16, 1916,

76 Baltimore Methodist, July 15, 1920.

77 Interview with Elaine Hamilton O’Neal, August, 2002.

Acknowledgements:

Robert F. Bailey is an historian with the Maryland Park

Service. His historical research paper, Scientific Forestry

And Urban Progressivism: The Development of the Maryland Board of Forestry, 1906 to 1921,

is not the property of the Department of Natural Resources and is being

re-printed on the DNR website as part of Maryland DNR's Centennial Notes series,

with the express permission of Robert F. Bailey who holds the copyright to his

work. No part of this document may be re-printed or copied for any use

without the written permission of the author.

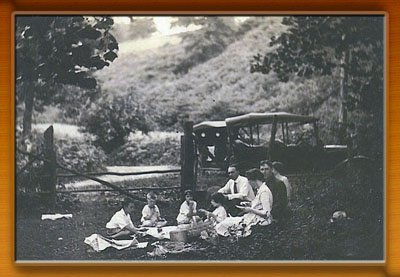

Photographs (top to

bottom):

Family camping on Patapsco Forest Reserve

Tree-lined Patapsco Watershed

Family Picnic in Patapsco Forest Reserve

Hutzler's Ice Cream Tent at Patapsco Forest Reserve