Scientific Forestry And Urban Progressivism:

Scientific Forestry And Urban Progressivism:

The Development of the Maryland Board of Forestry, 1906 to 1921

by Robert F. Bailey

Spreading the Gospel of Scientific Forestry

The Forestry Board’s decision to

hire Fred Wilson Besley was perhaps as significant as the creation of the

Forestry Board itself. Besley would serve as Maryland State Forester for 36

years—providing the Board (and later the Department) of Forestry with a

stabilizing force. Described by his descendents as humorless and strict, with a

penchant for noting meticulous detail, Besley’s personality was perfectly suited

for the rigors of the forestry profession.20

The Sun, impressed by Besley’s

resume, reported that “he did practical field work in nearly all branches of

service, embracing a field extending from Maine to Texas as far west as

Colorado.” His experience in the west “gave him a wide acquaintance with the

problems of city water supplies by means of tree planting on denuded mountain

watersheds.”21 Offered the State Forester position in May 1906,

Besley recalled fifty years later that “My first reaction to the offer was no. .

. . I knew something about politics in Maryland and I didn’t want a political

appointment. State forestry was so new, however, it was a challenge. When I was

assured it was independent of politics, I accepted.”22

Despite

not being a political appointee, his task was nevertheless challenging. Hired to

protect and manage existing forest reserves and to spread the gospel of

scientific management, Besley soon found himself confronted with a limited

operating budget, a small support staff dominated by volunteers, and an

apathetic legislature.

Despite

not being a political appointee, his task was nevertheless challenging. Hired to

protect and manage existing forest reserves and to spread the gospel of

scientific management, Besley soon found himself confronted with a limited

operating budget, a small support staff dominated by volunteers, and an

apathetic legislature.

Besley was charged with the task of slowing and/or

preventing a timber “famine,” but he had no power to control land-owners’

cutting habits, nor a subsidy available to dissuade owners from cutting. He was

entirely dependent upon his ability to educate the general public about the

benefits of scientific forestry. In the 1908/09 biannual report, Besley wrote,

“our forest area is so large so generally distributed that the average person

has the idea that timber is so abundant that there can never be a scarcity. It

is only by acquainting the public generally with the actual facts

showing the amount of timber we have, the rate that it is being used and the

present rate of growth of the forests, that the increasing scarcity is

sufficiently emphasized.” To educate the public, a concerted public relations

campaign was necessary.

Fortunately, the forestry legislation directed that

Besley develop a forestry education program at the Maryland Agricultural

College. The curriculum at College Park included lectures, classroom work and

field demonstration work, all designed “for better the prospective farmer to

manage his woodlot successfully, and the mechanical engineer to understand more

fully the properties and uses of the different woods.” The curriculum was,

however, supplemental. “It is in no sense designed to train the student as a

professional forester, for which several years of special work would be

required.”23

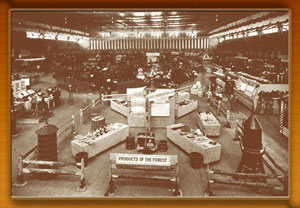

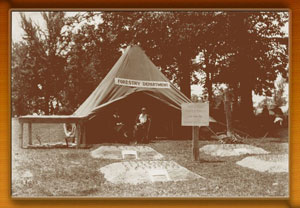

The college level lectures provided a natural springboard for public lectures—and there appeared to be a waiting audience. “In addition to the

regular lecture work,” the Board noted, “the State Forester has responded to the calls of various societies and organizations for lectures and addresses on

forestry.”24 Besley took full advantage of this education provision and made it a central element in the Forestry Board’s public relations campaign. Within a

few years, Besley and staff were giving dozens of lectures annually to “improvement societies, scientific bodies, trade organizations, colleges, high schools, academies and church organizations.”25 These lectures usually

culminated in an exhibit and display table at the Maryland Week Exhibition in

Baltimore. According to the Board, “the exhibit attracted much attention and led

to numerous inquiries. It has undoubtedly been the means of bringing

many people in touch with the work [of scientific forestry].”26

|

|

|

Forestry Exhibition in Baltimore Baltimore - Photo cut from 1912 - 1913

Report |

Forestry Tent Exhibit at University of Maryland Farmer's Day, Photo by Fred

W. Besley - May 26, 1923 |

Echoing the

philosophy of Gifford Pinchot’s National Forest Service, Besley’s propaganda

campaign was grounded in the idea that scientific forestry was not only

responsible, but profitable.27 Beginning in 1906, Besley began issuing leaflets

advertising “Practical Assistance to Owners of Woodlands.” For a nominal fee,

the State Forester and his assistants would survey private property and provide

advice on the best trees to remove and the best trees to plant. “The owner is

consulted as to the object of the management, whether for fuel, fence posts,

poles, ties, saw-logs, wind-breaks, soil protection, etc., or a combination of

these, and then the forester draws up a plan that will not only meet the

requirements of the owner, but also meet the needs of forest improvement.”

Furthermore, Besley argued in the leaflet that “It will be seen that forestry is

intensely practical, and that it should have a recognized place in farm

management.” To better illustrate Besley’s educational initiative, he concluded

that “The best way to introduce better forest management throughout the State is

to have object lessons in every neighborhood, to show what can be

accomplished.”28

Economic profitability remained a cornerstone of the Maryland

Forestry Board’s agenda for over a decade. In a feature published in the

Baltimore Sun on May 16, 1916, assistant State Forester J. Gordon Dorrance

articulated “The Romance of Forestry Science in Maryland.” The romance in this

instance was, of course, profit. In the article, Dorrance set up an

imaginary scenario whereby an ordinary, but contentious, farmer was faced with a

dilemma. A timber company offered the man a tempting $1,000 to clear-cut his

land. However, after allowing the Forestry Board to survey his property for a

mere $30 service fee, the farmer found that he could selectively cut the mature

and “defective” trees and turn a $3,000 profit (romance indeed!). Later that

same year, on June 26, the morning Sun reported on a concrete example in which

Miss Esther L. Cox of Union Bridge, for only $8.13, benefited from the Forestry

Board’s services. The Sun enthusiastically reported that “the full amount of the

estimated value [of the timber] was secured, and, the best of all, a future

stand of the right character of timber and the maximum production is assured.”

Driving the point home, the Sun wrote, “this give a very fair idea of what this

work accomplishes and what it costs.” By emphasizing that forestry was

profitable, Besley and Forestry Board were hoping to cultivate responsible

conservationist habits.

Economic profitability remained a cornerstone of the Maryland

Forestry Board’s agenda for over a decade. In a feature published in the

Baltimore Sun on May 16, 1916, assistant State Forester J. Gordon Dorrance

articulated “The Romance of Forestry Science in Maryland.” The romance in this

instance was, of course, profit. In the article, Dorrance set up an

imaginary scenario whereby an ordinary, but contentious, farmer was faced with a

dilemma. A timber company offered the man a tempting $1,000 to clear-cut his

land. However, after allowing the Forestry Board to survey his property for a

mere $30 service fee, the farmer found that he could selectively cut the mature

and “defective” trees and turn a $3,000 profit (romance indeed!). Later that

same year, on June 26, the morning Sun reported on a concrete example in which

Miss Esther L. Cox of Union Bridge, for only $8.13, benefited from the Forestry

Board’s services. The Sun enthusiastically reported that “the full amount of the

estimated value [of the timber] was secured, and, the best of all, a future

stand of the right character of timber and the maximum production is assured.”

Driving the point home, the Sun wrote, “this give a very fair idea of what this

work accomplishes and what it costs.” By emphasizing that forestry was

profitable, Besley and Forestry Board were hoping to cultivate responsible

conservationist habits.

Among the key components of the

Board’s legislative directives was a detailed survey throughout the state of

every tree stand five acres or larger. The work took Besley and his small team

to every county in Maryland, and by 1912 they had surveyed all but two counties.

“I’d hire a horse and buggy at a livery stable and jolt out along the dirt roads

as far as possible and then on foot follow the cow paths up through the woods

until I tramped over every woodlot above five acres in every county,” Besley

later recalled.29 The resulting survey maps provided a wealth

of detailed knowledge.

Yet, while Besley and his

assistants were surveying and collecting data, it had become apparent that the

State had provided no fiscal means with which to publish their findings.

Frustration over the State’s limited funding appropriations was evident by

1909. “There never was a greater need,” according to the Board’s Report for 1908

and 1909, “for the dissemination of information through publications and public

addresses. The people are ready for it. The Board of Forestry has the

information at hand, gained through its extensive studies of forest conditions,

but through a lack of funds it has been unable to publish it in a complete and

proper form.”30 Two years later, the Board’s biannual report

remarked that “The demands made [by], and opportunities presented [for the Board

of Forestry] are much larger than can be properly handled by the small

appropriation allotted, which have averaged only $4,000 annually for the past

five years.” The report concluded that at least a $10,000 appropriation was

necessary for the Board to continue its scientific forestry efforts.31

To address this conundrum, Besley

focused his efforts on cultivating key political allies. Despite this stern

character and his self-proclaimed unwillingness to deal with political

intricacies, Besley’s ability to further the scientific forestry cause would

have been limited without appealing to those with other agendas—in particular

urban progressives in Baltimore City and Baltimore County. By exploiting the

growing demand for recreational resources while simultaneously appealing to

urban romantic sentiments about nature, Besley was able to craft an effective

political alliance that furthered his scientific forestry agenda.

Molding the Landscape and

People —Urban Progressivism and Baltimore's City Parks

Meanwhile, as Brown, Besley and

others were establishing the Board of Forestry; a different kind of forest

preservation effort was taking place in Baltimore City and County. As several

scholars, including James B. Crooks, Sherry Olson and W. Edward Orser, have

argued, during the turn of the 20th-century, Baltimore’s social and business

elite, working through the Municipal Arts Society, combined conservationist

initiatives with real estate speculation to form a comprehensive plan for city

development. This plan, articulated by Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. and endorsed

by the Municipal Arts Society, encouraged suburban development through

protecting watersheds, finding new sources of drinking water, providing for

sewage treatment, and offering new sources of recreation.

Founded in 1899 by several of

Baltimore’s social and business elites, the Municipal Arts Society of Baltimore

City initially sought to “beautify the city” with decorations such as sculptures

and shade trees.32 As its membership increased, however, its

agenda became more substantive. Soon the Society’s membership was badgering the

local and state governments into providing for a modern sewer system.33

Then in January 1902, the Society hired the Olmsted Brothers architect firm to

draw up a development scheme for the City’s 1888 Annex.34

During this period, much of Baltimore’s middle and upper classes were moving

away from the city’s center and into the rolling hills closer to Baltimore

County—and in some cases, were spilling into Baltimore County. The Society hoped

that a development plan would help the annex retain its rural-like ambiance.

Also, learning from the congestion and infrastructure problems that plagued the

city’s older districts, the Society hoped that a planned approach would result

in a community that would not need rebuilding in later generations.35

Founded by the renowned landscape

architect Frederick Law Olmsted, by the early 20th century, control of the

Olmsted firm had been passed on to his son Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. The plan,

according to Crooks, “was a masterpiece that served as a basis for park

development for two generations.” Consisting of 120 pages, “the report,

illustrated with maps, gave substance to the Municipal Arts society’s ambitious

vision: to create numerous small parks and playgrounds, expand the larger city

parks, develop parkways and stream valley parks in the suburbs, and select and

set aside large reservations beyond the metropolitan area for future use.”36

According to Orser, “even though the charge of the plan was to concentrate on

the suburban zone, its recommendations took account of the needs of the complete

city.”37

In more detail, the Olmsted, Jr.

divided the city’s parks into five broad categories: reservations, country

parks, urban parks, district playgrounds and neighborhood playgrounds.

Tree-lined parkways and other “special facilities” such as zoos and golf courses

were included.

Reservations consisted of the lands

lying beyond the city’s borders that Olmsted recommended the City purchase in

advance of suburban development. These future parks would be accessed by roads,

but would initially not be developed for intensive recreation. Until suburban

expansion, the reservations would retain their rural character and serve the

city’s water-supply needs. According to Orser, “new park areas should be chosen

in such a way as not to interfere with development, but rather to enhance it. .

. . If land along streams could be purchased in advance of development, not only

would acquisition costs be low, but bringing them under public control would

prevent unwise private uses and save the city expensive infrastructure costs.”38

In short, less cost equaled more potential for profit. The Patapsco and

Gunpowder valleys received this designation.

The Olmsted plan stood on the cusp

of when park use began to shift from being primarily a place of contemplation to

a place of active physical recreation. The other four types of parks reflected,

in varying degrees, this mixed agenda. Located in stream valleys such as the

Gwynns Falls, the country parks were designed to give the visitor a sense of

being isolated from civilization. “The Baltimore report,” according to Orser,

“stressed the ‘enjoyment of outdoor beauty’ as a principal purpose of parks and

a value that should govern the design of large parks whose ‘essential value lies

in the contrast which they afford to urban conditions.’”39

Among Olmsted’s recommendations was that city buildings be hidden from park

vistas. The other three park types outlined by Olmsted were also to provide city

residents with temporary respites from the urban environment (borrowing

from country parks), but they would also offer playing fields for both men and

children. Indeed, playgrounds consisted of a third of the acres designated in

the plan.40

Despite Olmsted’s efforts to

address the city as a whole, the later four park types effectively reinforced

the city’s growing class (and racial) segregation. According to Orser, “There is

no doubt that the 1903 Olmsted reports did provide a framework for

suburbanization at a moment when the trend toward out-migration of the more

affluent was accelerating . . . leading to higher degrees of spatial separation

along lines of socioeconomic class.”41 Therefore, despite

Olmsted’s attempt to build parks throughout the city, the larger outlying parks

clearly favored white middle-class residents seeking to simultaneously escape

the congesting central city and embrace the benefits that stream valley parks

afforded. The advent of automobiles, which initially benefited the middle and

upper classes, only served to strengthen the middle-class orientation to

outlying suburban parks. This trend was naturally extended to the Patapsco

Valley.

The country parks, especially the

ones on the city’s periphery, served a growing middle-class desire to assert

their autonomy and independence, while demonstrating that they were physically

tough and rugged.42 Employed in white collar jobs, the growing

middle class, despite being more financially secure than their working-class

counterparts, nevertheless had to grapple with the reality that they were just

as subject to the elite’s whims. At the same time, however, because their jobs

were less physically demanding, there were concerns that their physical

conditioning might decline. Caught in-between the elites and working classes,

the middle class saw the country park as a place to demonstrate—at least

symbolically—that they were as physically tough as the working class, while

being as independent and intellectually refined as the elite.43 A

park in this sense, therefore, was every bit the refuge that Olmsted intended—a

place for both intellectual contemplation and exercise. Unlike the elite’s

Victorian Era retreats, where rugged physical activity was largely confined to

men, the country park experience, though segregated by gender, was shared

relatively equally. The Patapsco camping experience, for example, was, by and

large, a family affair.

The elite probably had a strong

interest in feeding this middle-class ambition. Some stood to profit from the

suburban development that was anticipated to crop up around the country parks,

but it is also plausible that the elite viewed this as a means in which to

maintain the social order. Olmsted’s parks, regardless of intention, in practice

served both the elite’s philanthropic, ideological and practical needs.

20 Kirk Rodgers, Besley’s grandson, noted Besley’s humorless demeanor in an

interview on January 20, 2004. Besley was also described as a staunch

Presbyterian and a strict disciplinarian. Few photos of Besley, if any, feature

him cracking a smile. Besley graduated with an engineering degree from the

Maryland Agricultural College in 1892, but the mid-1890s depression limited his

options. For six years he worked as a school teacher and deputy treasurer in

Virginia. Then, in 1898 a chance meeting with Gifford Pinchot convinced him to

pursue a career in scientific forestry. “Pinchot was so boiling over with

enthusiasm about forestry,” Besley remembered years later, “that then and there

I adopted forestry as my career.” Besley’s subsequent indoctrination into

forestry consisted both of field work and college. Pinchot included Besley among

his select group of 61 students that assisted the National Forest Bureau in

surveying and collecting data throughout the nation. During winters in

Washington D. C., Besley attended the famed “Baked Apple and Gingerbread Club”

lectures at Pinchot’s home. After several years of field work, Besley formalized

his educational credentials at the recently endowed Yale University School of

Forestry in 1903-04, and then polished his skills by doing field work for the

National Forest Service in Nebraska and Colorado. For more on Besley’s

biographical sketch, see American Forests Magazine, 38, 77-84 and the Baltimore

Sun, September 9, 1907.

21 Baltimore Sun, September 9, 1907.

22 American Forests Magazine, 82.

23 Report for 1906 and 1907, 4.

24 Report for 1906 and 1907, 4.

25 Report for 1910 and 1911, 7.

26 Report for 1910 and 1911, 7.

27 For more on Pinchot and the profitability of scientific forestry, see Robert E. Wolf, “National Forest Timber Sales and the Legacy of Gifford Pinchot: Managing Forest and Making it Pay,” in Char Miller, ed., American Forests: Nature, Culture, and Politics, (Lawrence, Kansas: University of Kansas Press, 1997), 87-105.

28 Report for 1906 and 1907, 13-14.

29 American Forests Magazine, 38.

30 Report for 1908 and 1909, 4.

31 Report for 1910 and 1911, 31.

32 Crooks, 129-130. To get a sense of the Society’s membership,

Crooks reports that a survey of the Society’s 122 organizers revealed 28

lawyers, 23 financiers (11 bankers), 40 businessmen, 12 artists and architects,

and seven professors from Johns Hopkins University.

33 During this period the turn of the century, Baltimore was the last

American city of comparable size without an improved sanitary sewer system.

Several members of the Society, including Society director Mendes Cohen, played

a key role during these critical years in badgering the City Council and the

State legislature for a substantive plan. Initially stymied by partisan

bickering, the sewer supporters eventually won over the city’s voters in a

referendum in 1906. Crooks, 136-137.

34 To recapture disappearing tax base that was settling in

suburban belt in Baltimore County, Baltimore City twice annexed land from the

County—in 1888 and 1918. For more on Baltimore’s political annexations, see

Joseph L. Arnold, “Suburban Growth and Municipal Annexation in Baltimore,

1745-1918,” Maryland Historical Magazine, 73(2), (June 1978), 109-128.

35 Crooks, 136-137. Arnold, 112-114.

36 Zucker, 82.

37 Orser, 478.

38 Orser, 476-477. 39 Orser, 475.

40 Orser, 470.

41 Orser, 477-478.

42 Defining class structures can be a complex task. In this article, the

middle class is defined as white men (and their families) who relied on the

elite for income, but made respectable wages working in jobs that did not

require demanding physical labor. Sales clerks, book-keepers and lower level

managers are examples.

43 Roderick Frazier Nash, Wilderness and the American Mind, (New

Haven: Yale University Press, 2001), 141-160. Though Nash’s interpretation is

not based on class divisions, he does articulate that there was a burgeoning

interest among city-dwellers to become reacquainted with outdoor living. Paul S.

Sutter, Driven Wild: How the Fight Against Automobiles Launched the Modern

Wilderness Movement, (Seattle: University Washington Press, 2002), 19-48. Sutter

makes a stronger connection between class and the growing interest in the

wilderness by linking it to the popularization of the automobile and efforts to

market the wilderness as part of America’s growing consumer culture.

Acknowledgements:

Robert F. Bailey is an historian with the Maryland Park

Service. His historical research paper, Scientific Forestry

And Urban Progressivism: The Development of the Maryland Board of Forestry, 1906 to 1921,

is not the property of the Department of Natural Resources and is being

re-printed on the DNR website as part of Maryland DNR's Centennial Notes series,

with the express permission of Robert F. Bailey who holds the copyright to his

work. No part of this document may be re-printed or copied for any use

without the written permission of the author.

Photographs (top to

bottom):

Southern Maryland Forestry Tour at Bowie Plantation. A Group of well-dressed

men touring a pine plantation. 1920's. Photo courtesy of U.S. Forest Service

Forestry Exhibition in Baltimore Baltimore - Photo cut from 1912 - 1913

Report

Forestry Tent Exhibit at University of Maryland Farmer's Day, Photo by Fred

W. Besley - May 26, 1923

Bringing in chestnut rails for hurdle fences. 1920's. Photo courtesy of U. S.

Forest Service