Scientific Forestry And Urban Progressivism:

The Development of the Maryland Board of Forestry, 1906 to 1921

by Robert F. Bailey

On Saturday morning, April 16, 1921, a pair of canoes sat resting on a bank near the gently flowing Patapsco River. To the east, the sun struggled to pierce the

gray clouds and misty fog blanketing the valley floor. Remnants of the sun’s light

dispersed through the budding box elders, sycamores and rock elms and cast the canoes in a patchwork of faint shadows. The temperature was balmy—about 60 degrees—and would

remain so for the rest of the day; topping out at 69 by late afternoon.1 The tranquil sound of the cool water sweeping over the rocks belied the scene’s industrial

heritage. Twenty years earlier, this location featured constant human activity, punctuated by the

rhythmic sound of machinery. Now, the hollowed walls of the deserted Orange

Grove Flourmill stood in crumbling defiance against the encroaching trees,

Virginia creeper and poison ivy.2 Only the railroad tracks, located

directly behind the mill’s ruins, and the occasional passing steam-powered

train, contrasted this scene’s garden-like ambiance. Baltimore City, though only

a dozen miles distant, seemed a world away.

|

|

|

Patapsco Orange Grove Area in Snow, March 1920, photo by Fred W.

Besley |

Fishing on the Patapsco near Relay, 1922, photo by Fred W. Besley |

Later that morning, the sound of an approaching automobile further eroded Orange

Grove’s apparent isolation. In the auto were six men who sought to paddle the

waiting canoes down the Patapsco to its confluence with the Middle Branch in

Baltimore. These men, however, were not typical weekend adventurers. The

expedition included: Frederick W. Besley, Maryland State Forester, Robert

Garrett of the Baltimore Municipal Arts Society and various representatives from

the State Board of Forestry, Baltimore City and the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad.3

These men aimed to explore the feasibility of constructing a “parkway” that

would connect the Patapsco Valley with Baltimore City. Yet, they did not wish to

completely reverse nature’s reclamation efforts. They hoped to make the valley

more accessible while allowing it to retain its natural ambiance. A journey down

the river itself, they anticipated, might reveal a better sense of the valley’s

scenic and recreational value, as well as the cost for acquiring the riverfront

property.

After the men disembarked from their auto, they shoved the canoes into the river

and boarded. There were three men in each canoe, with Besley and Garrett

wielding the stern paddles. After skillfully negotiating the rocky currents, the

men paused two miles downriver at Avalon, where they portaged the canoes around

Avalon Dam. Another vestige of the valley’s industrial heritage, the dam had

been refurbished by the Baltimore County Water & Electric Company to provide

fresh drinking water to residents in southwestern Baltimore County and City.

While at Avalon, Boy Scout Troop number 158 greeted the adventurers and provided

them with lunch. The Baltimore Sun reported that the “various State officials

and their guests seemed to get a lot of enjoyment out of wieners and beans.”

River Road Near Avalon

Patapsco

Forest Reserve, June 1920

After leaving Avalon, the men continued their journey down the Patapsco. The

balmy temperatures and persistent cloud cover made this an ideal day for

canoeing. Along the way, the men witnessed the river transform from a swiftly

moving rocky stream into a gently flowing river surrounded by marshlands. After

several hours of paddling, the expedition crept into the Middle Branch and in

the late evening they arrived at the Ariel Rowing Club. Their journey was a

success. According to the Sun, “repeatedly members of the party exclaimed over the beauty of the scenery.” They

were particularly enamored by the Cascade Falls near Orange Grove. The heavily

wooded landscape was also intriguing.4 Besley concluded, though

perhaps inaccurately, that the land had never been cut-over. More significantly,

however, the expedition was optimistic about acquiring the riverfront property.

Though they still lacked an exact cost estimate, Besley believed that the

$12,000 left in the Forestry Board’s land purchasing fund would be adequate.

Where land could not be purchased, he was confident cooperation with landowners

could be secured. Over the next few days, both the morning and evening editions

of the Sun eagerly reported on the proposed “Plan [for] Automobile Drive through

Beauty Spot,” and the “Plan to Preserve Banks of Patapsco.”5

“If the plan is realized,” the Evening Sun wrote, “it [the road] will continue a

section of the river for several miles up from the harbor which is now a source

of great pleasure for canoeists; will prevent the marring of the famous ‘River

road walk’ from Relay to Ellicott City, which has long been famous for its

beauty, and will provide a beautiful drive for motorists.” This last point was

especially exciting: the Evening Sun wrote that drivers would be able to “make a

circuit through the city park systems and through this Forest

Reserve, driving the greater part of the time through scenes of rare beauty.” 6

This canoe trip is one of many examples that illustrate the

Maryland State Board of Forestry’s close relationship with Baltimore’s

progressive economic elite. Beginning in 1912, State Forester Besley and Robert

Garrett, a partner in a leading banking firm and member of the Baltimore

Municipal Arts Society, had coordinated their efforts to improve access to the

Patapsco Forest Reserve’s recreational amenities. Besley and Garrett’s interests

were complementary. Besley sought to protect Maryland’s timber supply and

promote the benefits of scientific forestry to the general public. Garrett, a

former Olympian and avid promoter of outdoor activity and exercise, saw the

Patapsco Valley as a logical extension of the city’s growing park system. It was

Besley’s relationship with Garrett and other urban interests that helped make

the Forestry Board into a viable State institution.

Born out of a regional Western Maryland movement aimed at

protecting Maryland’s shrinking lumber reserves, prior to 1912 the Forestry

Board had been a cash-strapped appropriation struggling to fulfill its

legislative obligations. Following that year’s legislative session, however, the

Forestry Board’s operating budget more than doubled in 1913. By the decade’s

end, the Board’s appropriation was seven times larger than in it had been 1912.7

Besley’s willingness to accommodate the Baltimore region’s progressive impulses

was critical to this development. After 1912, the Forestry Board assisted urban

progressives by expanding the Patapsco Forest Reserve to meet the city’s need

for clean water resources, and by providing its citizens—especially middle-class

whites—with an additional recreational outlet. Both of these efforts the urban

elite hoped would facilitate suburban development.

This marriage, however, was not simply a marriage of

convenience. Their goals shared key fundamental aspects. They both believed in

the ultimate financial as well as environmental profitability of their

endeavors, they both sought government assistance to achieve their goals, and

they believed that their efforts would shape and mold human behavior—to a

degree, their success depended upon this last aspect.

My purpose here is to articulate the interdependent relationship

that developed between the Maryland Board of Forestry and the Baltimore City

urban elite. Most scholarship concerning the development of Maryland’s park

system, albeit limited, has

treated either Baltimore City or the state exclusively, with little regard for

how each entity interacted—a trend that characterizes a lot of Maryland

historical scholarship.8 In this case, not only did State and

Baltimore interests interact, but also this interaction proved to be a critical turning point in the development of a State institution.

Though it was intended to be—and ultimately became—a statewide

endeavor, it was those living in Western Maryland who acutely felt the need for

a more effective means of protecting and preserving the forestland. Despite

efforts by settlers to clear the land during the 18th and 19th-centuries,

Garrett County featured the most significant acreage of the Maryland’s remaining

forestland. Even as late as 1914, 63 percent of the county remained

wooded—though a considerably smaller percentage of that was “virgin.” According

to Besley, “the good quality of the land early attracted settlers, and under the

constant influx of immigrants, the best of the suitable lands have been

cleared.” The county’s mountainous terrain deterred settlers from completely

clear-cutting it. “The forests have, therefore,” wrote Besley, “receded from the

valleys and are now mostly confined to the mountains and rugged slopes.”9

Though early settlers had left their imprint on the landscape, their land

clearing efforts typically did not include river valleys where the rugged

geography made farming impractical.

Though it was intended to be—and ultimately became—a statewide

endeavor, it was those living in Western Maryland who acutely felt the need for

a more effective means of protecting and preserving the forestland. Despite

efforts by settlers to clear the land during the 18th and 19th-centuries,

Garrett County featured the most significant acreage of the Maryland’s remaining

forestland. Even as late as 1914, 63 percent of the county remained

wooded—though a considerably smaller percentage of that was “virgin.” According

to Besley, “the good quality of the land early attracted settlers, and under the

constant influx of immigrants, the best of the suitable lands have been

cleared.” The county’s mountainous terrain deterred settlers from completely

clear-cutting it. “The forests have, therefore,” wrote Besley, “receded from the

valleys and are now mostly confined to the mountains and rugged slopes.”9

Though early settlers had left their imprint on the landscape, their land

clearing efforts typically did not include river valleys where the rugged

geography made farming impractical.

Turn-of-the-century lumber companies, however, saw the treed

landscape as an untapped economic resource, and began making significant inroads

into the region by the 1880s.10 Late 19th and early 20th century

timber companies typically clear-cut land with little regard for conservation or

environmental ramifications.11 The detrimental effect of

indiscriminate cutting was the result of several timber companies competing for

increasingly scarce resources. This development was further exacerbated by the

nation’s insatiable demands for timber. For many communities in Appalachia, a

devastating domino effect resulted. Denuded lands led to increased sediment

runoff, clouding stream and river water and simultaneously killing the fish and

destroying valuable sources of drinking water (in many areas, the runoff mixed

with poison waste from strip mines). The sediment runoff then proceeded to back

up mill dams and clog drainage channels. With less water absorbing into the

ground—a valuable function provided by trees—there was a rise in the frequency

of both flooded (during wet seasons) and dry (during dry seasons) streams and

rivers. Increased runoff also lowered the water table and cut further into

drinking water supply. Add to this mix a growing human population capable of

producing more sources of waste, organic and non-organic, and the result in many

areas were literal cesspools of disease and poverty.

By 1905, local newspapers such as the Oakland Republican

began to articulate the need to protect the county’s environment—particularly

its timber, game and fish reserves. In response, Garrett County voters that year

sent William McCulloh Brown to the State Senate with a bill providing for

the creation of a State Board of Forestry. According to the Baltimore Sun,

“Mr. Brown lives in Garrett County, where the lumber interests are large and

where the fountain head of many streams are situated. He finds that the forests

of his county are the finest and most extensive in the State, are rapidly

disappearing before the sawmill.” Expressing confidence in his legislation, the

Sun reported that Brown “is satisfied that the State should own large

forest preserves which would not only be a source of profit to the State in the

future, but would also preserve game birds and animals from extermination.”12

By 1905, local newspapers such as the Oakland Republican

began to articulate the need to protect the county’s environment—particularly

its timber, game and fish reserves. In response, Garrett County voters that year

sent William McCulloh Brown to the State Senate with a bill providing for

the creation of a State Board of Forestry. According to the Baltimore Sun,

“Mr. Brown lives in Garrett County, where the lumber interests are large and

where the fountain head of many streams are situated. He finds that the forests

of his county are the finest and most extensive in the State, are rapidly

disappearing before the sawmill.” Expressing confidence in his legislation, the

Sun reported that Brown “is satisfied that the State should own large

forest preserves which would not only be a source of profit to the State in the

future, but would also preserve game birds and animals from extermination.”12

Introduced in February 1906, Browns’ forestry bill was passed

virtually unaltered on March 31. The forestry bill stipulated the creation of a

Board of Forestry that consisted of the Governor, Comptroller, President of

Johns Hopkins University, President of Maryland Agricultural College, State

Geologist, “one citizen of the State known to be interested in the advancement

of forestry,” and “one practical lumberman engaged in the manufacture of lumber

within this State.”13 Though the legislation gave the Board of

Forestry the legal power to purchase private property, the bill was nevertheless

conservative. To ameliorate elements who may have harbored concerns about the

State purchasing land, the bill empowered the state to indirectly

conserve, manage and control Maryland’s timber supply. Therefore, during its

early years, all State Forest Reserves would consist of philanthropic

donations—and beyond a 2,000 acre tract in Garrett County and a 43 acre tract in

Baltimore County, few donations were forthcoming.14 With a miniscule

$3,500 annual appropriation, the Forestry Board lacked the financial muscle

necessary to purchase land. In fact, its appropriation was barely large enough

to hire one professional forester and a small supporting staff. Accordingly, the

Board of Forestry’s two primary functions involved fighting forest fires and

acting as a scientific forestry information clearing house until 1912.

The legislation empowered the Board of Forestry to hire a

professional State Forester to “have direction of all forests, and all matters

pertaining of forestry” in Maryland. The State Forester was to direct all forest

wardens, initially consisting of unpaid volunteers, and “aid and direct them in

their work.” Foremost among the forester warden’s duties included putting out

and preventing forest fires and apprehending and prosecuting those responsible

for starting fires. “When any forest warden shall see or have any reported to

him a forest fire, it shall be his duty to immediately repair to the scene of

the fire and employ such persons and means as in his judgment seem expedient and

necessary to extinguish said fire.”15

The Forester’s advisory role reflected the faith that scientific

forestry was, indeed, profitable. According to the legislation, the State

Forester was to “co-operate with counties, town, corporations and individuals in

preparing plans for the protection, management and replacement of trees,

woodlots, and timber tracts, under an agreement that the parties obtaining such

assistance pay at least the field expenses of the men employed in preparing said

plans.”16 A few altruistic people aside, it was unlikely that

corporations and individual landowners would have been compelled to seek and pay

for state assistance unless there was the potential for profit. In selling his

forestry bill to the Senate, Brown argued, “the forester studies the soil and

climatic conditions, finds out what species of trees are best adapted to a

particular locality, and will make the most rapid and profitable growth

on any particular tract. . . .He is thus of practical value to the lumberman and

to private owners of the forest lands” (my italics).17

Though the legislation failed to explicitly reference the

forests’ value in protecting streams and rivers, Brown encouraged his colleagues

to consider that benefit when weighing the decision. Brown argued that “the

forest, with its dense foliage and carpet of moss and ferns, acts as a reservoir

to store up and regulate the moisture, which comes in the form of rain.” To

drive his point home, Brown romantically analogized that “springs are the

children of the forest, and as they unite into brooks, streams and rivers those

are the most regular in their flow and volume, and these conditions are directly

influenced by the forest.”18

Pleased with the legislative session, the Sun opined that

“the Forestry bill is designed to promote the scientific study of the forest

resources of Maryland and their bearing on the water supply. It should produce

good results.”19

1 Baltimore Sun,

Morning, April 17, 1921.

2 Orange Grove

Flourmill, Mill C of the Patapsco Manufacturing Company, burnt on May 8, 1905.

For more on the history of Orange Grove during its industrial

period, see Thomas L. Phillips,

The Orange Grove Story; A View of Maryland Americana in 1900,

(Washington, D. C.: The Author, 1972). The narrative here it based on photos taken a few years after mill

burnt (which are included in Phillips’ The Orange Grove Story), and my observations of the native tree

and vine species that presently grow there.

3 In addition to Besley and Garrett, the party also included K. E.

Pfeifer, Assistant State Forester, Edmund George Prince, Patapsco Forest Reserve

warden, Joseph W. Shirley of the Baltimore City Topographical Survey Commission,

and Alva Day of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad.

4 In addition to the ubiquitous tobacco plantations, the Patapsco

River had once boasted several charcoal-fired iron mills during the late 18th

and early 19th centuries. These mills consumed considerable

quantities of timber on a daily basis, and it is unlikely that they would have

left any nearby timber stands untouched.

5 Baltimore Sun, Morning, April 16, 17, and 18, 1921,

Baltimore Sun, Evening, April 16 and 20, 1921. Both Sun papers gave

fairly detailed accounts of the events on April 16, 1921, but their accounts

vary. According to the Morning Sun, the expedition was larger, and it went

directly by automobile to Avalon, where they Boy Scouts provided them lunch, and

the men walked about a mile downriver to Relay, where they embarked on their

canoe expedition. The Evening Sun’s reporting closer reflects the

narrative given here. Since the Morning Sun recounts the expedition’s

enchantment with the Cascade Falls, which are located near Orange Grove, I am

more inclined to agree with the Evening Sun’s interpretation.

6 Baltimore Sun,

Evening, April 20, 1921.

7 The Board of Forestry’s operating budget was $4,000 in 1912,

$10,000 in 1913, and $28,580 in 1921. Totals were taken from the Report of

the Maryland State Board of Forestry for 1912 and 1913 and the

Report of the Maryland State Board of Forestry for 1920 and 1921.

The totals are not adjusted for inflation.

8 For previous scholarship on the development of Baltimore’s park

system, see: James B. Crooks, Politics and Progress: The Rise of Urban

Progressivism in Baltimore, 1895 to 1911, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State

University Press, 1968), 127-154, Sherry H. Olson, Baltimore: The Building of

an American City, (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997), 245,

249-258, W. Edward Orser, “A Tale of Two Park Plans: The Olmsted Vision for

Baltimore and Seattle, 1903,” Maryland Historical Magazine, 98(4),

(Winter 2003), 467-483, Kevin Zucker, “Falls and Stream Valleys: Frederick Law

Olmsted and The Parks of Baltimore,” Maryland Historical Magazine, 90(1),

(Spring 1995), 73-96, and Barry Kessler and David Zang, The Play Life of a

City: Baltimore’s Recreation and Parks, 1900-1955, (Baltimore: Baltimore

City Life Museums and the Baltimore City Department of Recreation and Parks,

1989). For previous scholarship on the development of the Maryland State Board

of Forestry, see: Geoffrey L. Buckley and J. Morgan Grove, “Sowing the Seeds of

Forest Conservation: Fred Besley and the Maryland Story, 1906-1923,” Maryland

Historical Magazine, 96(3), (Fall 2001), 303-327, Ralph R. Widner, ed.,

Forests and Forestry in the American States: A Reference Anthology,

(Washington D. C.: The National Association of State Foresters), 145-152,

236-245, Ney C. Landrum, ed., Histories of the Southeastern State Park

Systems, (Washington D. C.: Association of Southeastern State Park

Directors, 1992), 80-91, and American Forests Magazine, (October 1956).

9 F. W. Besley, The Forests of Garrett County,

(Baltimore: Maryland State Board of Forestry, 1914), 7-8.

10 Besley, The Forests of Garrett County, 7. In 1914, Besley

argued that the bulk of the region’s virgin pine forests were cut 35 to 40 years

before.

11 Several scholars have recounted the detrimental effects of

“unscientific” forestry methods. See, Geoffrey L. Buckley, “The Environmental

Transformation of an Appalachian Valley, 1850-1906,” Geographical Review,

88(2), (April, 1998), 175-198, Ronald L. Lewis, Transforming the Appalachian

Countryside: Railroads, Deforestation, and Social Change in West Virginia,

1880-1920, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998) and

Thomas R. Cox, Robert S. Maxwell, Phillip Drennon Thomas, and Joseph J. Malone,

This Well-Wooded Land: Americans and Their Forests from Colonial Times to the

Present, (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1985).

12 Baltimore Sun, April 1, 1906.

13 The Maryland Agricultural College later became the University of

Maryland College Park.

14 These two tracts consisted of a 1,917 acre tract donated by Robert

and John W. Garrett, and a 43 acre tract donated by John M. Glenn. The Garrett

deed stipulated that “if within the period of next twenty five years from this

date hereof, the said State of Maryland should neglect or fail to carry out the

provisions of said Forestry Act, or abandon the property hereby donated, then

the title to the said several tracts and parcels of land shall revert to the

said donors.” Summary of Deed, Garrett Bequest to State of Maryland,

Maryland Hall of Records.

15 Laws of Maryland, Chapter 294, Section 6,534.

16 Laws of Maryland, Chapter 294, Section 4,533-534.

17 Oakland Republican, March 1, 1906.

18 Oakland Republican, March 1,

1906.

19 Baltimore Sun, April 4,

1906.

Acknowledgements:

Robert F. Bailey is an historian with the Maryland Park

Service. His historical research paper, Scientific Forestry

And Urban Progressivism: The Development of the Maryland Board of Forestry, 1906 to 1921,

is not the property of the Department of Natural Resources and is being

re-printed on the DNR website as part of Maryland DNR's Centennial Notes series,

with the express permission of Robert F. Bailey who holds the copyright to his

work. No part of this document may be re-printed or copied for any use

without the written permission of the author.

Photographs (top to

bottom):

Patapsco Orange Grove Area in Snow, March 1920, photo by Fred W.

Besley

Fishing on the Patapsco near Relay, 1922, photo by Fred W. Besley

River Road Near Avalon, Patapsco Forest Reserve, June 1920, photo by Fred W.

Besley

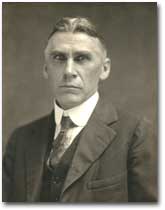

Fred W. Besley, Maryland's First State Forester

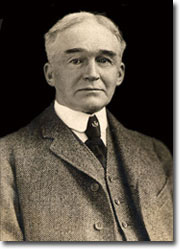

William McCulloh Brown, Maryland State Senator