History of Maryland State Parks: The Short Course

By Ross Kimmel and Offutt Johnson

Maryland’s state forests and parks system will mark its 100th anniversary this year. On March 31, 1906, the State legislature passed Maryland’s first forestry law, and Governor Edwin Warfield signed the bill the following April 5. Maryland was thus the third state in the Union to establish a program of scientific forest management, and, almost immediately, our present system of state parks began as an offshoot of the that forestry program.

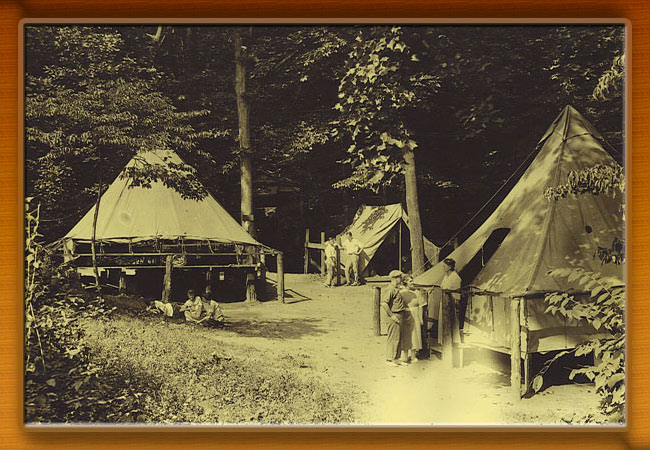

By 1910, the State forester was informally calling the then very small Patapsco Forest Reserve “Patapsco Park.” By 1912, a portion of that forest/park had been developed and dedicated specifically for public recreational use. Campers, picnickers, and swimmers flocked out of Baltimore to rusticate alongside the Patapsco River. Now a 14,000 acre, 32 mile long state park, Patapsco serves annually about 575,000 visitors. Patapsco’s history represents in microcosm the history of how Maryland’s parks developed.

By 1910, the State forester was informally calling the then very small Patapsco Forest Reserve “Patapsco Park.” By 1912, a portion of that forest/park had been developed and dedicated specifically for public recreational use. Campers, picnickers, and swimmers flocked out of Baltimore to rusticate alongside the Patapsco River. Now a 14,000 acre, 32 mile long state park, Patapsco serves annually about 575,000 visitors. Patapsco’s history represents in microcosm the history of how Maryland’s parks developed.

.jpg)

So does Fort Frederick State Park’s history. It too was technically a “forest reserve” but functioned more as a park. In 1922, the State purchased a farm in Washington County that had on it Fort Frederick, a ruined relic of the French and Indian War, which historic preservationists wanted protected and restored by the state. And indeed there were forestry practices carried on there. The real purpose of this acquisition was not so much to serve the forestry agenda but an effort to appease influential historic preservationists who wanted the fort preserved as public property and made into a park. One of those preservationists had been instrumental in creating Maryland’s forest/park service. Fort Frederick, now officially a park, is a 600-acre tract, with the partially restored fort, and annually serves 127,000 visitors, especially history lovers.

Now, let’s put this story of the beginning of state forestry and parks in its historical context. Why did it happen when it did? The answer, briefly, is two-fold:

- the deplorable condition, in the early 20th century, of Maryland’s forest reserves, all of which were privately owned; and

- the resolve of key individuals (including politicians, philanthropists, and certain state officials) to rectify the situation. Two and a half centuries of rapacious civilization, and especially the tactics of get-rich-quick/cut-and-run lumberman, had left the state with scarcely a stand of first growth timber. Unchecked forest fires and erosion worsened the situation.

To challenge Maryland State government into doing something about this situation, brothers John and Robert Garrett, who were heirs to part of the B and O Railroad fortune and were investment bankers in their own right, donated nearly 2,000 acres of cut-over land in Garrett County to the state on the condition that the state institute policies and governmental machinery to begin scientific management of this and other potential Maryland forest resources. The state responded accordingly, passing a forestry law in 1906 establishing an official Board of Forestry to oversee acquisition and wise management of this and other forest reserves, provide for a system of forest fire suppression, hire a state forester, and to provide technical assistance to private owners of woodlots. Three key people inside of state government helped frame and pass this law: State Senators William McCulloh Brown of Garrett County, Joseph B. Seth of the lower Eastern Shore, and State Geologist W. Bullock Clark. (The Garrett bequest is now part of Potomac-Garrett State Forest in Garrett County.)

Though the six-page forestry law is mostly about forestry, tucked in it, in a section detailing the duties of the state forester, is reference to “the protection and improvement of State parks and forest reserves.” Other than that, there is nothing specific about state parks, but clearly the founders had something in mind. The following year, 1907, another publicly spirited citizen named John Glenn donated 43 acres along the Patapsco, the nucleus of Patapsco Forest Reserve, which would very shortly emerge as Maryland’s first state park.

A priority for the newly-created Board of Forestry was, of course, the appointment of Maryland’s first State forester, whose responsibility was to execute the will of the legislature under direction of the Board of Forestry. The job fell to a young man named Fred W. Besley, a Yale-trained professional forester and protégé of Gifford Pinchot, the famous first U.S. Forester. Besley would serve as Maryland’s State forester until he retired in 1941 at age 70.

A priority for the newly-created Board of Forestry was, of course, the appointment of Maryland’s first State forester, whose responsibility was to execute the will of the legislature under direction of the Board of Forestry. The job fell to a young man named Fred W. Besley, a Yale-trained professional forester and protégé of Gifford Pinchot, the famous first U.S. Forester. Besley would serve as Maryland’s State forester until he retired in 1941 at age 70.

Besley deserves great credit for establishing both scientific forest conservation and a system of state parks in Maryland. He was an indefatigable advocate of wise forest conservation, even long after his retirement. One of his first accomplishments as state forester was personally to find, inventory and record every stand of trees in the state larger than five acres! It took him years of traveling by train, horse and foot, later recalling “I tramped every cow path in Maryland.” In 1916 he published in a memorable book, The Forests of Maryland, the results of his work. Fred Besley was the embodiment of ethical public service and natural resource conservation.

Now, the reason Patapsco and Fort Frederick Forest Reserves had park uses folded into their development was that, early on, Besley seized upon the recreational potential of state forest reserves as a way to promote the general concept of forest conservation, and herein lay the origins of Maryland State Parks. Since early in the 19th century, Americans had romanticized nature as a venue for spiritual renewal and inspiration. Towards the end of that century, as the real frontier disappeared, there arose an ethic of vigorous outdoor exercise as a way to improve both mind and body. President Theodore Roosevelt was a well-known advocate of this ethic. Fred Besley too subscribed to the rugged outdoor life ethic, at least to the extent it could help him further the forestry agenda. A local paper quoted Besley as describing Patapsco as “a real place to ‘rough it pleasantly.’” In 1916, one of Besley’s assistants, J. Gordon Dorrance, wrote in The Baltimore Sun that the working man’s “vacation weeks are the most important of his year,” adding that “muscles softened by disuse must be rebuilt by exercise and unaccustomed ‘stunts’ to which man has grown a stranger.”

Aligning himself with prominent Baltimore political and social elites, State Forester Besley sought ways to promote the growing Patapsco Forest Reserve as a place for outdoor recreation as sort of a city park outside of the city. As we have seen, by 1912, parts of Patapsco, which Besley and others informally called “Patapsco Park,” had developed camping, picnicking and swimming facilities. Some Baltimore families took to camping in the park all summer, with the family wage earners commuting into the city each workday via train. Hutzler’s Department Store actually reserved a number of campsites for its employees to spend their summers in the park with their families. Besley himself spent most of one summer camping at Patapsco with his family (an experience his surviving daughter does not remember too pleasantly).

Meanwhile, Fred Besley and the Board of Forestry continued to accept State forest land donations, and by the 1910s were receiving state monies for forest purchase. At the same time, with the advent of the automobile and the easy times of the 1920s, the public desired more recreational access to forest preserves and parks. In fact, the main thing that predicates public parks is a public with leisure time and disposable income, both of which were commonplace by the early 20th century, thanks to the Industrial Revolution and the rise of a moneyed middle class. State parks, to supplement growing national parks, helped supply the demand. Stephen Mather, the first director of the National Park Service, was a strong advocate of systems of state parks to supplement the burgeoning system of national parks.

In 1923, Governor Albert C. Ritchie overhauled the state’s unwieldy system of 85 independent boards and commissions, such as the Board of Forestry, reducing them to 14. Forestry, in the form of a five-man forestry advisory board, was placed under auspices of the Board of Regents of the University of Maryland, because that body was regarded as non-political (Besley fought hard to keep politics out of forestry), and because Besley was teaching forestry at the University and had, in fact, established the first state tree nursery there. Besley and his nascent staff became the Department of Forestry, charged with executing the forestry policies of the Board of Regents, acting on advice from the forestry advisory board.

This arrangement continued satisfactorily until 1936 when H.C. “Curly” Byrd assumed the presidency of the University of Maryland. Charismatic, egotistical, energetic and cunning, Byrd was dedicated to building a first class institution, and little interested in forestry. He sought to dominate forestry – and its budget – by ordering Besley and his staff to relocate from Baltimore to College Park. The Forestry Advisory Board resigned in protest, and the whole issue became a hot political one in the state. Besley refused to relocate. The impasse was the subject of many editorials, and at least one political cartoon, in The Baltimore Sun, which disliked Byrd intensely. The forest wardens and other concerned Marylanders appealed to Governors Harry Nice and, later, Herbert R. O’Conor, as well as to the Board of Public Works. Finally the legislature provided relief in 1941 by consolidating all state conservation agencies, including forestry, under a new Board of Natural Resources, totally independent of the University.

.jpg) The 1941 law took cognizance of the emergence of parks in forests. It recast the old forestry department as the Department of State Forests and Parks. Besley was succeeded in 1941 by Joseph F. Kaylor, another trained forester who was styled Director of State Forests and Parks.

The 1941 law took cognizance of the emergence of parks in forests. It recast the old forestry department as the Department of State Forests and Parks. Besley was succeeded in 1941 by Joseph F. Kaylor, another trained forester who was styled Director of State Forests and Parks.

Kaylor was a strong advocate of stream valley state parks, like Patapsco and Gunpowder. His assistant, H. C. Buckingham, worked avidly to fund the development of recreation areas within forest reserves, especially at New Germany and Herrington Manor. Still, even though parks now had official parity with forests, for two more decades the forestry agenda would dominate.

By the early 1940s, considerable Maryland public forest lands had been developed for recreational use as parks, thanks to the Civilian Conservation Corps. The CCC was a massive Federal works program during the Great Depression. In Maryland, the CCC put a total of 30,000 young men to work reclaiming natural resources, restoring historic sites, and building facilities for public accommodation in the out of doors. The CCC built lakes, cabins, pavilions, trails, campgrounds and other visitor amenities all over the state, though principally in Western Maryland. The C’s also restored Fort Frederick’s wall and reconstructed the Washington Monument (originally built in 1827) near Boonsboro. Herrington Manor, Swallow Falls, New Germany, Washington Monument, Gambrill, Fort Frederick, Patapsco, Elk Neck and Pocomoke State Parks were the primary beneficiaries of CCC park development, and in fact, most of the CCC-built facilities are still in use across Maryland’s state forests and parks.

Following the cataclysmic events of the Great Depression and World War II, with the demobilization of the military, the baby boom, and the return of prosperity, and an increasingly mobile American public (cars, roads and leisure time), there was a boom in public demand for outdoor recreational opportunities.

The Department of State Forests and Parks tried responded as best as it could. In 1954 it created the position of Superintendent of State Parks and filled the position with a landscape architect named William R. Hall, who was succeeded in 1956 by William A. Parr, another forester. In addition there was a major commitment to expand state park lands. Patapsco Forest Reserve was rededicated in its entirety as a state park. Sandy Point, on the Bay, and Cunningham Falls, at Catoctin Mountain, were established as state parks. Restricted budgets and domination of parks by foresters, however, had a depressive effect on the evolution of a strong park component within the department. Then, in 1961, a special “Commission of [State] Forests and Parks” recommended long-term goals and strategies for state park development. While some park areas were to be developed for fairly intensive recreational use, many others were to be left relatively untouched to preserve their natural beauty for public enjoyment. The Commission’s final report was the first master plan for an expanded system of Maryland state parks.

Despite the dominance of a forestry agenda and the recommendations of the Commission of Forests and Parks, the early 1960s saw a new emphasis upon park development. In 1962, Governor J. Millard Tawes established separate divisions of forests and parks within the department. Moreover, Spencer Ellis, a landscape architect and a dedicated park professional was brought in as director of the entire department. Now, for the first time, a park person was in charge of state forests and parks and this would auger a change in departmental emphasis from forestry to parks. Ellis’s assistant director for state parks, A.J. Pickall, and Pickall’s immediate successor, William H. Johnson, were foresters, but were as dedicated to park development as was Ellis. In any case, from the early 1960s on, state parks were to begin a 30-year period of active acquisition and development.

President Lyndon Johnson pronounced the 1960s the age of “The Great Society.” Government, through activist policies and massive taxation, could and should tend to all manner of social needs, in addition to providing traditional services such as national defense. Among the various social needs was the public demand for recreation. This agenda received impetus and justification from Laurence Rockefeller’s Outdoor Recreation Resource Review Commission, which concluded that federal and state authorities were failing to meet the public’s demand for outdoor recreational opportunities. Mechanisms were accordingly established to funnel massive federal aid to states for this purpose.

Meanwhile, under the direction of Spencer Ellis, the Maryland Division of State Parks built a large staff of young, professional park planners to prepare a bold new program of state park land acquisition and capital development. Master plans tumbled forth proposing golf courses, swimming pools, lodges, visitor centers, amphitheaters and other ambitions amenities to be funded and built in state parks. The Maryland Outdoor Recreation Land Loan Act of 1969, which established Program Open Space, along with Federal aid, made possible accelerated park acquisition, but there was never a concomitant commitment of funding for facility development or - especially- for operation and maintenance.

Program Open Space imposed a one-half of one percent tax on all real estate title transfers in Maryland, with the proceeds dedicated to the acquisition and development of parklands. Half the money was retained at the state level for land acquisition only, and the other half went to counties and municipalities, which could use their share for both acquisition and development. A unit named “Program Open Space” handled acquisition for the state and parceled out the local governments’ shares. Additional matching funds came from a Federal source called the Land and Water Conservation Fund, which vastly increased the largess. Learn more about the role played by the iconic emblem for Program Open Space, Woody Duck.

Program Open Space imposed a one-half of one percent tax on all real estate title transfers in Maryland, with the proceeds dedicated to the acquisition and development of parklands. Half the money was retained at the state level for land acquisition only, and the other half went to counties and municipalities, which could use their share for both acquisition and development. A unit named “Program Open Space” handled acquisition for the state and parceled out the local governments’ shares. Additional matching funds came from a Federal source called the Land and Water Conservation Fund, which vastly increased the largess. Learn more about the role played by the iconic emblem for Program Open Space, Woody Duck.

In its first twenty years, Program Open Space added nearly 60,000 acres to Maryland’s state park holdings, a 57% increase. POS was reauthorized in 1989, and is yet augmenting state park holdings, though since the 1980s, federal matches have dropped off precipitously. POS has been wildly successful in saving natural lands from loss due to commercial and residential development. For better or worse (probably better), the legislature only fully funded six of the ambitious master plans of the 1960s: Point Lookout, Cunningham Falls, Greenbrier, Shad Landing now Pocomoke River, Elk Neck, Rocky Gap, and Deep Creek Lake State Parks; others were only partially funded, and many not at all.

While park staffs have remained small, the exigencies of modern times have required greater emphasis upon levels of training and professionalism among park managers, rangers, technicians, naturalists and historians. In the 1970s, with the crime rate growing across America, including state parks, the decision was reluctantly made to train rangers as law enforcement officers, and to arm them. Then, in 2004, park rangers were transferred to the Natural Resources Police.

Meantime, state government continued to reorganize the governmental machinery that administered parks. In 1969, Governor Marvin Mandel adopted a cabinet form of government for the state and established today’s Department of Natural Resources, with a cabinet level Secretary to report to him (former Governor J. Millard Tawes was the first Secretary of Natural Resources). Once again, all of the state’s disparate natural resources management entities were consolidated under the new Department of Natural Resources. The functions of the old Department of State Forests and Parks were subsumed under DNR, and in 1972 those functions were split into three distinct agencies, the Maryland Forest Service (under Pete Bond), the Maryland Park Service (with Bill Parr once again in charge of parks), and the Capital Programs Administration (under Deputy Secretary Louis N. Phipps, Jr.), which handled capital acquisition (including Program Open Space) and capital development.

Upon the retirements of the directors of forests and parks, about 1978, the two agencies were united under Donald E. MacLauchlan, Bill Parr’s assistant director of parks, a trained forester who was nevertheless devoted to parks. Eventually, DNR’s wildlife component was added, but the arrangement proved unwieldy. After MacLauchlan’s retirement in 1991, wildlife and cooperative forestry were split out of the park equation. Dave Hathway became Park Service director after MacLauchlan. Following Hathway’s retirement in 1991, Rick Barton became Superintendent of State Forests and Parks. In 2004, most park rangers were transferred to the Natural Resources Police, and in 2005, the four state forests reverted to the Maryland Forest Service, with today’s Maryland Park Service emerging again as its own separate agency.

Today, Maryland’s State parks, natural resources management areas, and natural environment areas comprise over 130,000 acres of public land (two percent of Maryland’s land mass). Two-hundred and three full-time and 400 seasonal employees care for these public lands. State park resources are diverse and include, besides natural wonders, a number of highly significant historic sites. But state parks’ single most important resource is, and always has been, the people who care for them. Most importantly, we must remember to value our visitors to these natural resources. Without general public visitation, we would not be in our positions. We must all work together to preserve these valuable lands, rich in history and that is going back to Fred Besley in 1906.

Photos (top to bottom)

- Hutzler's Camp on the Patapsco Forest Reserve

- Fort Frederick 1937 Ceremony

- Fred W. Besley, Maryland's 1st State Forester, surveying

- Joseph Kaylor, 2nd from the left, Maryland's 2nd State Forester

- Program Open Space early emblem: Woody Duck